Dive into Android TA Bug Hunting And Fuzzing

Preface

The presentation was selected by OffensiveCon 2023, but due to certain restrictions, I was unable to travel outside of China to attend these security conferences at that time. Therefore, I had to cancel the presentation. I can only give presentations at Chinese security conferences.

The topic was first presented at Kanxue SDC 2023 in Shanghai, China on October 23, 2023. Later, it was presented at the Huawei Security Reward Program Annual Conference 2024 in Shenzhen, China on March 28, 2024. There were some minor changes in the Huawei presentation. I added a few previously undisclosed details.

I was focusing on bug hunting and fuzzing on Android and IoT. However, when I disclosed the vulnerabilities, I found that Android OEMs have poor vulnerability disclosure policies and offer lower bug bounties. Even if I can achieve system or root LPE on Android, the bug bounty may only be $1k, and they don’t want me to disclose the vulnerabilities or even mention that their products have vulnerabilities. Finding these vulnerabilities feels like doing charity work. Of course, Huawei is an exception; they handle vulnerability disclosure better and offer appropriate rewards.

During this research, I built a system for simulating and fuzzing Android Trusted Applications based on AFL + Unicorn. I believe this system is general enough to be efficiently used for macOS/iOS vulnerability research as well. All I need to do is implement the syscalls and APIs for the macOS/iOS platform and use the appropriate architecture to simulate the binaries. Additionally, I’ve heard that Apple’s vulnerability disclosure policy is more open and offers higher rewards, so I began shifting my research focus to Apple’s products, such as macOS, starting in July 2023.

As a farewell to my previous research, I decided to restate this topic in English today.

The slides locate at https://github.com/guluisacat/MySlides/tree/main/KanxueSDC2023

Introduction

In recent years, the Trusted Execution Environment (TEE) has become increasingly prevalent in the Android ecosystem, encompassing smartphones, smart cars, smart TVs, and more. The TEE operates an independent and isolated TrustZone operating system that runs parallel to Android. This ensures that core sensitive user data and essential security policies of the phone remain secure, even if the Android system is compromised.

Similar to the system-level apps pre-installed in the Android system, the TEE system also houses necessary applications, known as Trusted Applications (TAs). These applications are responsible for implementing security strategies, such as data encryption. In the second half of 2022, the speaker conducted a security study on the TA implementations of some mainstream manufacturers. To date, 60 vulnerabilities have been confirmed, including but not limited to the extraction of fingerprint images, bypassing fingerprint lock screens, extracting payment keys, and retrieving users’ plaintext passwords.

In this article, the speaker will introduce the implementation of TAs in the TEE environments of mainstream manufacturers, along with common attack surfaces. Additionally, tips and methods for conducting security research on TAs will be shared, such as how to quickly obtain a smartphone with root access for research and testing. During the study, the speaker developed a simulation system for emulating and fuzzing these TAs. This article will also cover the implementation of this simulation system, the fuzzing techniques used, and some tuning strategies.

Table of Contents

- What is TEE and What it Can Do?

- Analysis and Reverse Engineering of Mainstream TA Implementations

- How to Conduct Security Research on TAs

- Simulation of TAs

- Fuzzing of TAs

- Attack Surface of TAs

1. What is TEE and What is Can Do?

Before we dive into TEE vulnerability bug hunting and fuzzing, we need to understand some basic concepts of TEE.

1.1 What is TEE?

Trusted Execution Environment, which is an independent security area located within the main processor.

1.2 What Does TEE Do?

- TEE provides an isolated environment for running applications within it, protecting these applications and data from attacks by other software. TEE is often used to process sensitive data such as passwords, keys, and biometric data.

- Even if the device’s main operating system is compromised, the sensitive data and security policies stored in the TEE will not be affected.

1.3 What is Normal World and REE?

- Refers to the device’s main operating system environment, including the running applications and the operating system itself. This environment typically includes various user applications and services, but it is not considered secure because it can be subject to various attacks.

- In this presentation, both

Normal WorldandREErefer to theAndroid.

1.4 What is CA?

Client Application (CA), these applications run in the device’s main operating system (i.e., Normal World) and communicate with the TEE (also known as Secure World) through specific APIs.

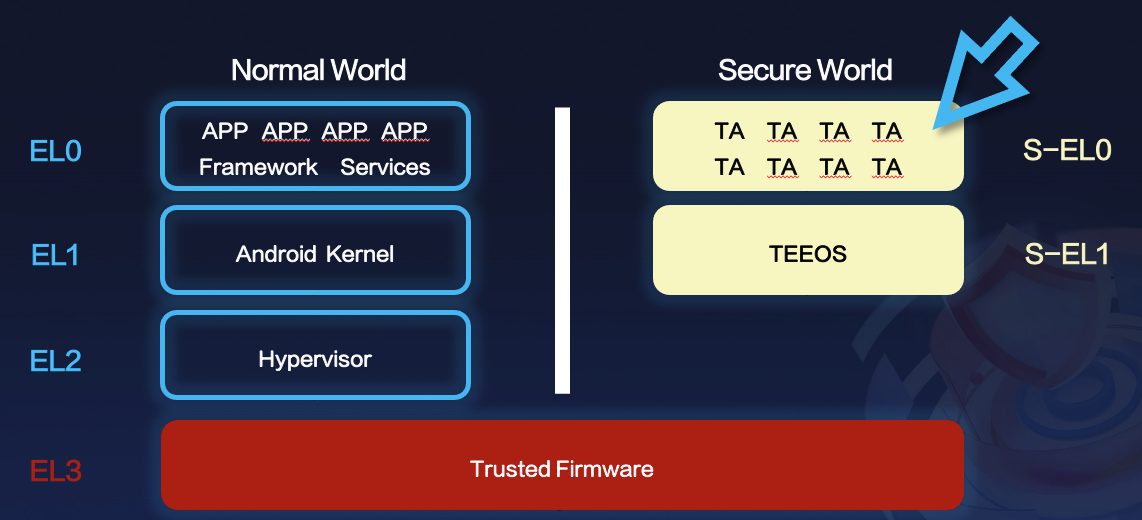

1.5 General Architecture

This is a general architecture for TEEs. Different TEE implementations have some differences in their architecture.

For example, Kinibi TEE includes trusted drivers at the S-EL0 level.

In this talk, I’m focusing on S-EL0's bug hunting and fuzzing.

1.6 The Role of TAs

In Android, pre-installed or system applications like SMS, System Settings, Contacts, and Camera provide basic functionalities to meet users’ needs.

For TEE, it is primarily used for secure storage of sensitive data, secure communication, encryption policies, DRM, and rendering trusted user interfaces. The entities responsible for implementing these functions are known as Trusted Applications.

Additionally, if we were app developers, ensuring that our app’s core security logic remains intact on a rooted device could be achieved by considering the use of TAs.

1.7 Why I Conducted Security Research on TAs

- In the second half of 2022, I initially intended to conduct vulnerability research on the entire ecosystem of TAs, TEEOS, and ATF.

- However, while researching TAs, I discovered an unexpectedly high number of vulnerabilities, prompting me to focus on the TAs of several mainstream vendors.

- By March 2023, 60 vulnerabilities had been confirmed (including collisions). Due to manufacturers’ vulnerability disclosure policies and bounty issues, I stopped my research on TAs. Hence, the simulation and fuzzing system in place could potentially unearth more vulnerabilities.

- Additionally, due to the limitations imposed by manufacturers’ vulnerability disclosure policies, I have to omit certain details of these vulnerabilities in this sharing.

Objectives:

-

TEEs based on OP-TEE

-

MiTEE from Xiaomi

-

TAs developed by MTK

-

A custom-developed TEE from an anonymous Chinese smartphone manufacturer

-

Qualcomm, Kinibi

-

Huawei, Samsung:

-

At that time, other researchers had just started conducting security research on them and had already discovered many vulnerabilities

-

So there was structural analysis and simulating but no bug hunting yet

-

2. Analysis and Reverse Engineering of Mainstream TA Implementations

2.1 Understanding Communication Between CA and TA

Initially, the CA calls the TEE API to communicate with a driver on the Android. From a security design and implementation perspective, this Android driver must restrict access so that only processes with system or root privileges can interact with it.

The driver initializes the request, packages the necessary parameters, and sends them to the TEE via the EL3 : Secure Monitor.

Once the TEE receives the request, it loads the TA file into memory based on the type of TA. For instance, if it is a regular TA stored in the Android file system, the TEE will load the TA from the Android file system into memory. The TEE then verifies the integrity, certificate signatures, and version of the TA. If the verification passes, the TA can enter its lifecycle.

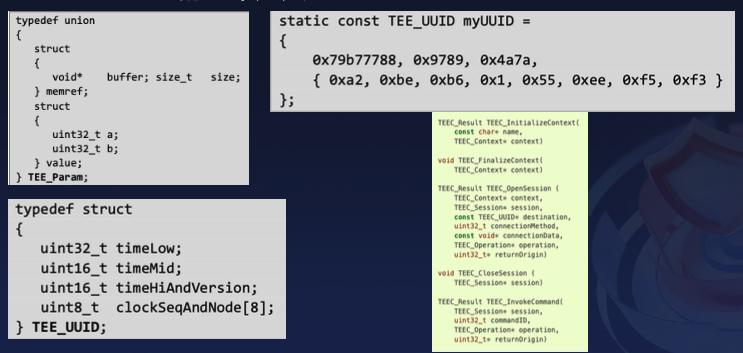

2.2 GlobalPlatform TEE Client API Specification

Before introducing the TA lifecycle, we need to understand a specification known as the GlobalPlatform TEE Client API Specification. This specification can be simply understood as a standardized development process.

If developers follow this specification, they can develop their own Trusted Applications and Client Applications quickly.

2.3 TA Lifecycle in the GlobalPlatform

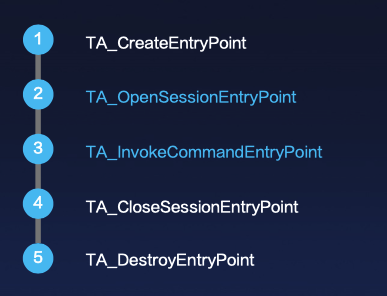

The TA lifecycle according to the GP (Global Platform) specification comprises mainly five stages.

For security researchers, our interest usually lies in the first three stages.

The TA_CreateEntryPoint and TA_OpenSessionEntryPoint stages are fundamentally for initialization.

The third function, TA_InvokeCommandEntryPoint, is our primary focus for analysis, as developers handle external data requests in this function.

Additionally,we need to care about TA_OpenSessionEntryPoint too because it can handle the external inputs as well, posing a potential vulnerability attack surface.

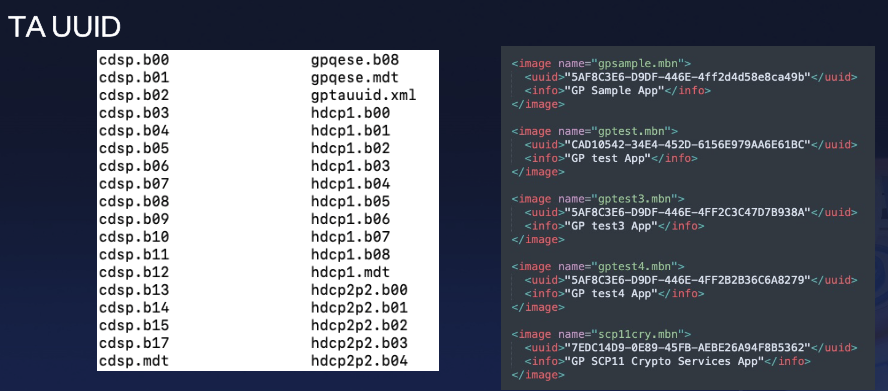

As we can see below, the TEE relies on UUIDs to identify different TAs.

On some phones using Qualcomm chips or with manufacturer-specific TEEs, we observe that TAs are identified by names that do not follow the UUID format. However, after reverse-engineering, we can find that they are essentially still UUID TAs, but with an additional layer of mapping on top.

2.4 Categorizing TAs

My research involved TAs developed by multiple vendors, each with different formats, APIs, and syscalls.

To facilitate simulation and fuzzing, I categorized these TAs based on how they receive and process external input data.

- TAs that Follow the Global Platform TEE Client API Specification

- Use the

TEE_Paramsstructure for data exchange. - Examples: MiTEE, HTEE, OP-TEE, and many other TEEs based on OP-TEE.

- Use the

- TAs that Use Proprietary Data Streams

- Read data from data streams.

- Vendors may implement their own data transmission and processing protocols.

- They may also follow Global Platform specifications with additional layers of abstraction, restricting the parameter types that can be passed to the TA.

- Examples: Qualcomm QSEE, Kinibi TEE.

2.5 How to Analyze the Communication Process Between CA and TA

Different TEE implementations have different communication processes.

It is better to teach a man to fish than to give him fish so I will share a common analysis method:

ps -A |grep ca

lsof -p $ca_pid

Sometimes we only need to use lsof to examine which .so files are loaded by the TAs’ CAs. The names of these shared libraries can quickly indicate their association with TEE APIs.

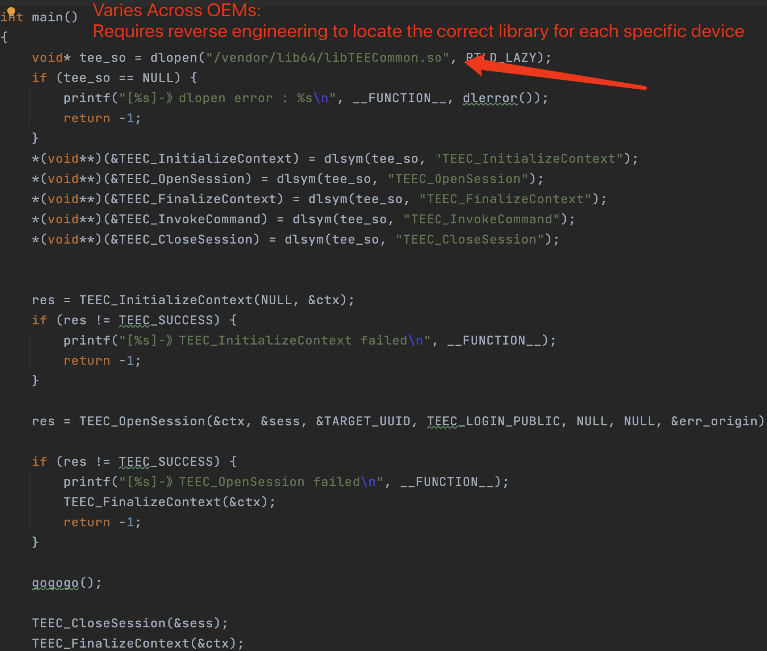

Global Platform API:

As we can see below, we can identify that libTEECommon.so is certainly related to TEE APIs. Therefore, we only need to use dlopen to load it and dlsym to call the functions within it.

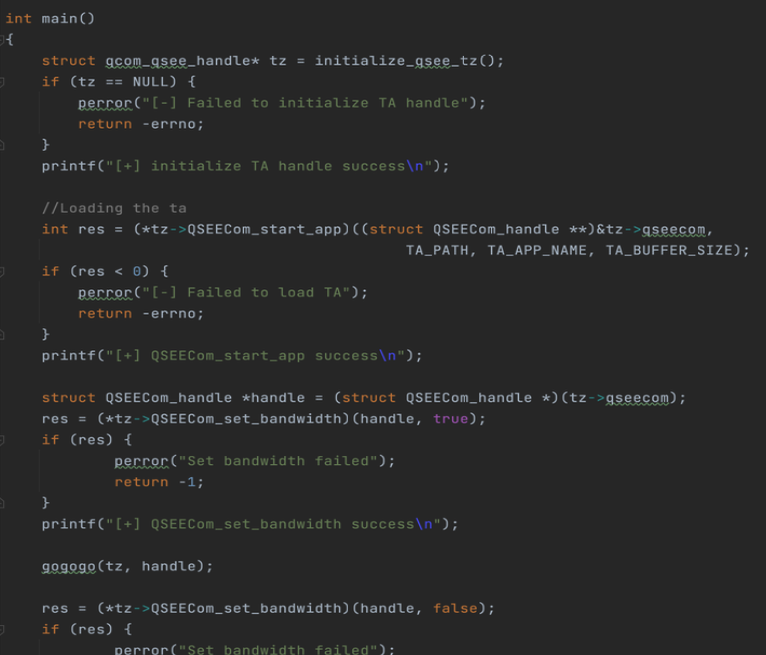

QSEE API:

Analyzing the API for Qualcomm TAs is much simpler because some of Qualcomm’s CAs are open source in AOSP. Therefore, we can directly analyze the source code and quickly determine the methods to call them.

2.6 Categories of TA Instances

Multi-Instance:

- Multiple CAs can simultaneously interact with the same TA, and each CA’s interaction does not affect the others.

- For multi-instance TAs, we need to pay extra attention to potential race conditions when accessing the same resource file.

Single-Instance:

- A TA has only one instance, and all CAs share this single TA instance. If one CA is interacting with this TA, other CAs must wait until the current interaction is complete.

- Single-instance TAs are often seen in Fingerprint TAs. During testing, it is recommended to use Frida to hook the CA, communicate with the TA, and then kill the CA to reinitialize the TA. This approach avoids complexity and saves effort.

2.7 Extracting TAs

Regular TAs:

- Extracting from the device (requires root access):

find / -path /proc -prune -o -path /dev -prune -o -path /mnt -prune -o -path /storage -prune -o -type f \( -name "*.ta" -o -name "*.sec" -o -name "*.tabin" -o -name "*.tlbin" -o -name "*.drbin" -o -name "*.mdt" -o -name "*.mbn" \) -print - Extracting from OTA firmware packages:

- NON-HLOS.img

- system.img/vendor.img/product.img/odm.img

Embedded TAs (such as some TAs in Samsung TEEGris):

- Analyzing and extracting from specific image formats of TEEOS.

- I speculate that some TAs, due to functional requirements, are loaded earlier than the initialization of the REE file system, or to improve runtime efficiency, hence they adopt the form of embedded TAs.

2.8 Reverse Engineer on TAs

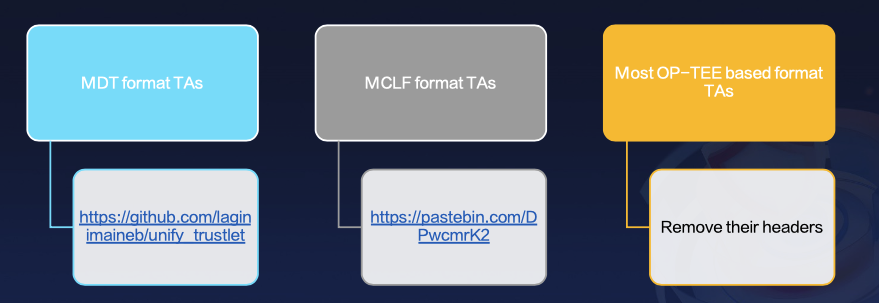

From my research, only Qualcomm and Kinibi have adopted custom formats for their TAs - namely, the mdt and mclf formats. Fortunately, there are comprehensive open-source solutions available on GitHub for these formats.

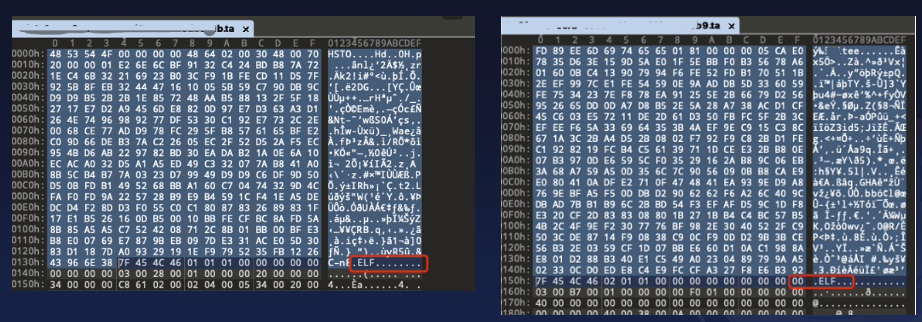

For TAs from other manufacturers, they predominantly use the OP-TEE format, which is relatively straightforward to analyze.

By simply removing the original TA header, these files can be directly analyzed in tools like IDA Pro.

Although some vendors’ TAs are encrypted and cannot be directly analyzed, once decrypted through certain methods, we can still find that they are based on the OP-TEE format.

OP-TEE format TAs often include an .elf file header within their binary content. By simply removing the TA header preceding the .elf file header, IDA Pro can correctly interpret and analyze the file.

However, this approach is primarily suited for reverse engineering, as the TA header typically contains crucial information such as the TA’s UUID and section data, which are essential for simulation. Therefore, for simulation purposes, we need to handle them on a case-by-case basis.

3. How to Conduct Security Research on TAs

3.1 Challenges in Conducting Security Research on TAs

- Difficult to debug TAs:

- TEE is independent of the Android system.

- Software debugging is almost impossible; some TEEs can only be debugged with hardware tools like JTAG.

- Logs of CA calls to TAs are often turned off or encrypted, making it difficult to know the results of CA requests:

- Logs are disabled or encrypted, making it impossible to know the execution results of CA requests.

- For example, if I discover a stack overflow vulnerability and write a PoC, I cannot determine the PoC’s execution result after sending it to the TA. This makes it challenging to know whether the PoC is useful.

- Most TAs contain sensitive content and functions, so only CAs with certain privileges can invoke TAs:

- Research requires gaining privileges, like Group, System or Root, to interact with the TA.

- Some vendors restrict access to specific TAs to certain processes only. This requires attackers to first escalate privileges to those specific processes or obtain kernel root access to communicate with the target TA.

So currently, TA security research is primarily conducted in two dimensions:

- On actual Android devices

- Using simulation tools

3.2 Bug Hunting on Actual Android Devices

We have three methods to create a research environment for testing TAs on real Android devices:

-

Gain System or root privileges

-

Use Nday or 0day vulnerabilities to unlock the bootloader

-

Use a stepping-stone app to perform the attack

In my research, I used the second and third methods to test.

I would also like to share some of my previous research using the first method. Three years ago, I developed a semi-automated static vulnerability scanning tool. With a sufficiently rich vulnerability template, it can automatically identify all potential local system/root privilege escalation points. A simple manual audit can then swiftly reveal most local system or root privilege vulnerabilities. This tool combines the advantages of “text-based matching” and “static taint analysis” for vulnerability scanning, balancing both false negative and false positive rates. Although better vulnerability scanning solutions are now available, considering the development time cost for researchers, this tool still holds certain advantages and can be quickly developed within two weeks.

https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/lnmqVQl8YUT_mPQuwqn5RQ

However, my blog on that topic is currently only available in Chinese, and I suggest using ChatGPT for translation. Additionally, I appreciate the technical sharing from the researchers mentioned in the blog. My blog serves as a supplement to their shared content, providing positive feedback to the open-source community. Due to some reasons, I could not fully disclose the details in that blog and could only share some insights. I hope these insights are helpful to others.

For local system privilege escalation and root privilege escalation vulnerability hunting, I suggest broadening our thinking.

I categorize vulnerabilities into two types:

- Vulnerabilities that can be weaponizd

- Vulnerabilities that can be used for security research

Since our goal at this moment is not to attack others but to create a research environment, we can actually focus more on vulnerabilities that are only useful for security research.

3.3 Attention: Local Privilege Escalation Vulnerabilities Useful Only for Security Research

-

Non-default configurations vulnerabilities

-

Vulnerabilities requiring pre-granted auxiliary functions

- Vulnerabilities requiring other sensitive privileges:

- For example, the

PendingIntent hijacking vulnerabilityin Android

- For example, the

- Other security vulnerabilities requiring multiple user interactions

A typical example is the PendingIntent hijacking vulnerability in notifications.

Exploiting this vulnerability requires the user to grant Notification Manager permission to our app in the settings beforehand. This permission-granting action is considered a strong interaction. Even if we successfully hijack the PendingIntent and can send arbitrary intents with system-level privileges, the vulnerability will be downgraded to medium or low severity due to the prerequisite of strong user interaction.

If a vulnerability requires multiple interactions, such as five or ten steps, vendors may not even fix it.

However, for security researchers, these vulnerabilities can become powerful tools for building our research environment.

3.4 Unlock Bootloaders

In my research, the primary method involved unlocking bootloaders to achieve persistent root access. The first consideration was whether unlocking bootloaders would be challenging.

Before diving into bootloader security research, I anticipated that it would require a significant time investment to unlock bootloaders for several mainstream manufacturers’ phones.

However, after conducting the research, I found that the difficulty was lower than expected. I successfully unlocked five phone models: 3 using Nday exploits and 2 with 0day exploits.

The prevalence of Nday exploits was surprisingly high, contrary to my initial expectation that more 0days would be needed.

Why?

Let’s take a moment to think carefully. If we aim to use Nday vulnerbailities for unlocking bootloaders to build our security research devices, do we need to target the latest flagship phones? Not necessarily.

Our targets can be old phones or sub-brand phones with the latest OEM systems, as our goal is simply to have a device with the latest system.

Therefore, we can actually try a wide variety of attack surfaces. We’re unconcerned with the phone’s version, configuration, or whether the exploit is weaponizable. Unlocking the bootloaders of such phones grants us the capability to test TEEs and TAs on real devices with the latest flagship models.

3.5 Unlock Bootloaders: 0 Day + NDay

On the other hand, if we don’t find a suitable target for Nday exploits, a combination of 0day and Nday exploits could be considered.

Repairing vulnerabilities that can unlock Bootloaders differs from fixing common vulnerabilities.

- If attackers unlock the Bootloader on an older system version, they can still gain root access by flashing the latest version of the system by themselves.

- In some cases, even with an unlocked Bootloader on an older system version, phones can be directly updated to the latest version, and the manufacturer’s OTA updates will not relock the Bootloader.

Therefore, repairing unlocked Bootloader vulnerabilities requires the vendor not only to provide the patch for the vulnerability but also to prevent users from downgrading to a vulnerable version.

Now mainstream manufacturers generally impose strict restrictions on phone downgrades:

- Some phones require users to upgrade through an intermediate package to upgrade to the specified version.

- Some phones require the use of downgrade tools provided by the manufacturer.

- Manufacturers provide some security measures to ensure the downgrade process is not bypassed, such as private keys, signatures, and downgrade keys.

But are the vendor’s downgrade strategies truly secure?

No.

- Phone downgrades are a common user demand, and considering security and user experience, vendors can easily compromise and provide exceptions for users. Our focus should be on finding such exceptions.

- A single security strategy is often insufficient.

Note: The vendors do not allow me to disclose the details of these vulnerabilities, so I have to omit this part.

Alternatively, I will introduce two attack surfaces.

3.6 Unlock Bootloader: Two Attack Surfaces

Unlock Bootloader:

- Simply put, the bootloader is an independent system. When it receives the firmware flashed by the user, it first needs to save it to its own buffer area before executing the flashing installation.

- If the developer handles firmware verification with global variable reuse vulnerabilities or race condition vulnerabilities caused by parallelism, and if a legitimate firmware and an illegal firmware are flashed consecutively or preemptively, this could result in the illegal firmware unexpectedly passing verification.

Mitigation Strategies:

- Many OEMs have developed Windows clients to handle downgrade operations. These Windows clients obtain encrypted firmware packages from the servers, decrypt them, and then push the decrypted packages to the mobile device. The mobile device then attempts to decrypt the encrypted packages.

- If we obtain an unencrypted firmware package in some ways, can we trigger the downgrade directly?

- Is the decryption and encryption process controlled by the client? If so, we can hook the Windows client and trigger the decryption process as we want.

4. Simulation of TAs

So far, we’ve discussed TA research on actual Android devices. Let’s now shift to TA simulation.

When it comes to TA simulation, Unicorn and Qemu are indispensable topics. I chose Unicorn.

4.1 Choosing: Qiling Framework or Develop My Own Framework Based on Unicorn

-

Option 1: Qiling Framework is developed based on Unicorn. It is currently very mature, providing many necessary functions to help developers quickly simulate and fuzz.

-

Option 2: Develop based on Unicorn by myself. The workload is larger, but the customization capability is stronger.

Conclusion:

- The goal of this research is to target mainstream TEE implementations, aiming to build a general simulation and fuzzing framework.

- Since each TEE has different syscall implementations, to avoid spending too much time on compatibility issues, I chose Option 2.

- However, if future research focuses on the security of TEEOS, I will switch to using the Qiling Framework.

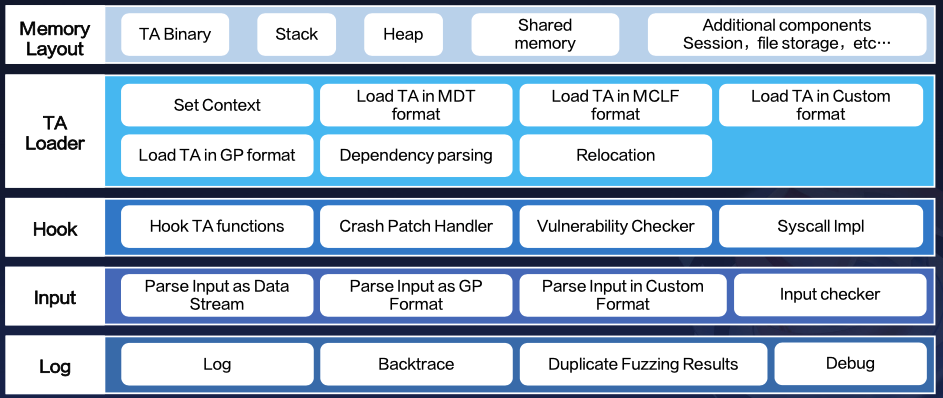

4.2 Architecture: My Simulation and Fuzzing Framework

Here’s an overview of the simulation and Fuzzing framework.

4.2.1 Crash Patch Handler

A crucial component to highlight is the Crash Patch handler within the Hook module.

This module was not part of the original architecture but became essential once Fuzzing commenced.

If a TA has numerous vulnerabilities, crashes caused by earlier code could hinder the effective testing of subsequent code.

The solution was to manually patch the TA with the Crash Patch Handler, such as adjusting the registers to safe values to prevent overflows or out-of-bounds errors during memcpy execution.

4.2.2 Redirection of Imported Functions

- Some TAs in TEEs rely on imported functions from external shared objects (so).

- These shared objects are part of the TEE system and do not exist in the Android file system; instead, they are packaged together with the TEEOS image.

- If we want to analyze and redirect these imported functions, we first need to crack the special format of the TEEOS image and extract the complete shared library.

- However, my research involves many mainstream Android OEMs. If I had to break them one by one, it would cost me a lot of time. I conduct the research on my own. Is there a simpler way?

Yes, we can start by identifying the assembly patterns.

To be honest, I did the research on my own, and there is too much work that needs to be done by myself. Therefore, if there is an easier way to solve a problem, I will always choose the simpler method.

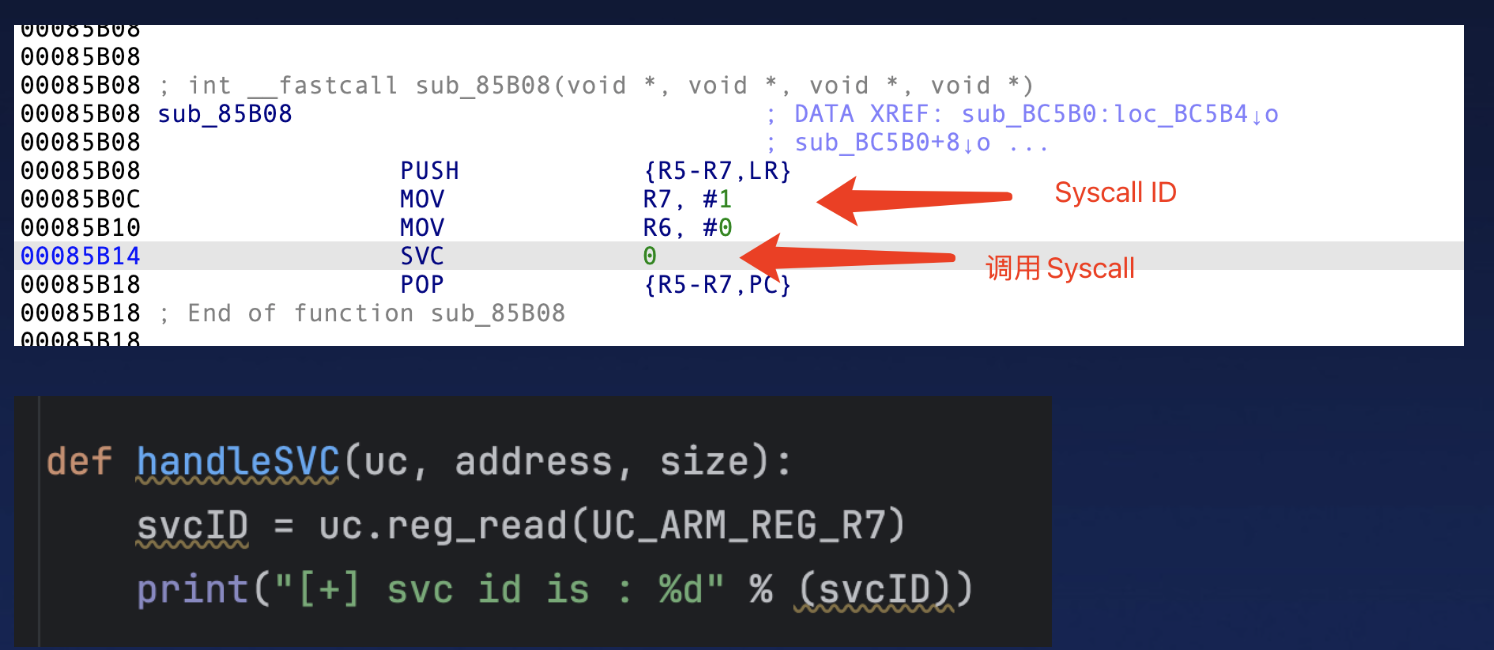

1. Redirection of Imported Functions : OP-TEE

- The TA format of OP-TEE is special, and all functions are inlined. Therefore, we only need to focus on the interception and implementation of syscalls.

- The assembly code that invokes syscalls has distinct characteristics.

2. Redirection of Imported Functions : TAs with Few External Dependencies

- Some TAs are highly encapsulated and rely on only a limited number of external functions, usually just 5 to 10, which can be handled by scripts or manually.

- These externam function calls follow the address resolution strategy of the

GOTandPLTtables.

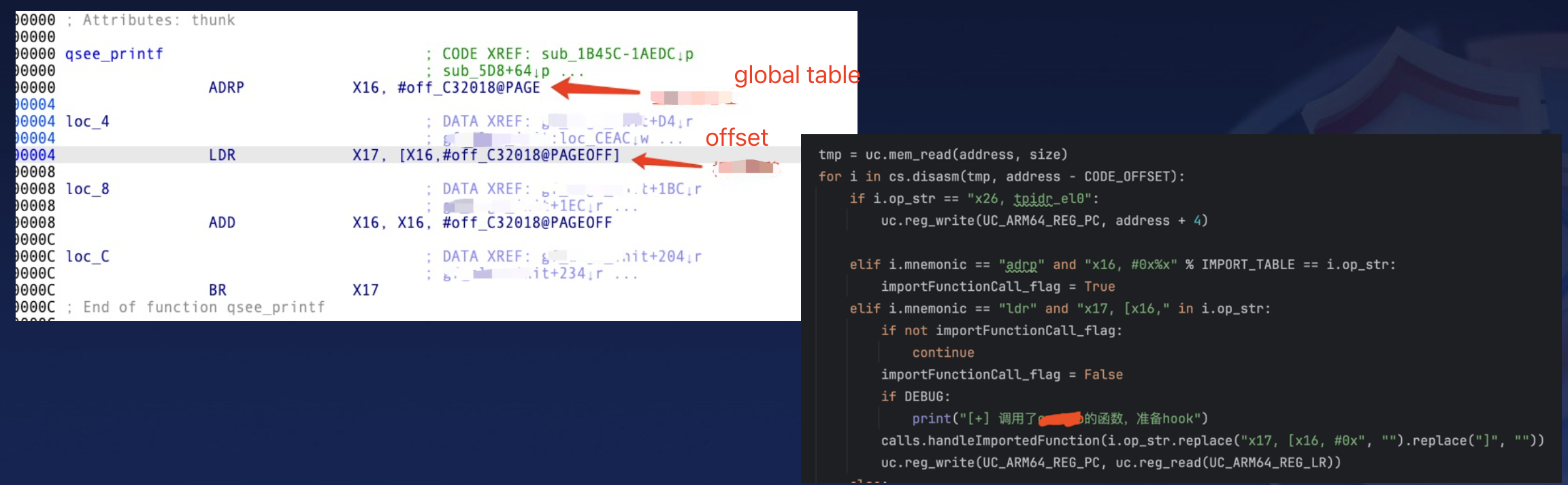

3. Redirection of Imported Functions : TAs with Extensive External Dependencies

- Examples: MiTEE and Samsung TEE

- Similar to programs on Linux, they rely on

libcand make extensive use of basic functions likeprintfandstrcpy. - We need to reverse engineer and decompress their TEEOSs, obtain the original dependency libraries, analyze and redirect the dependencies.

- For the sake of fuzzing efficiency, the lazy loading of shared objects needs to be modified to immediate loading.

5. Fuzzing of TAs

5.1 AFL-Unicorn

AFL-Unicorn was chosen for Fuzzing, but it has known issues, including :

- Stateless Fuzzing

- Crash-based vulnerability detection

- The lack of ASAN (AddressSanitizer)

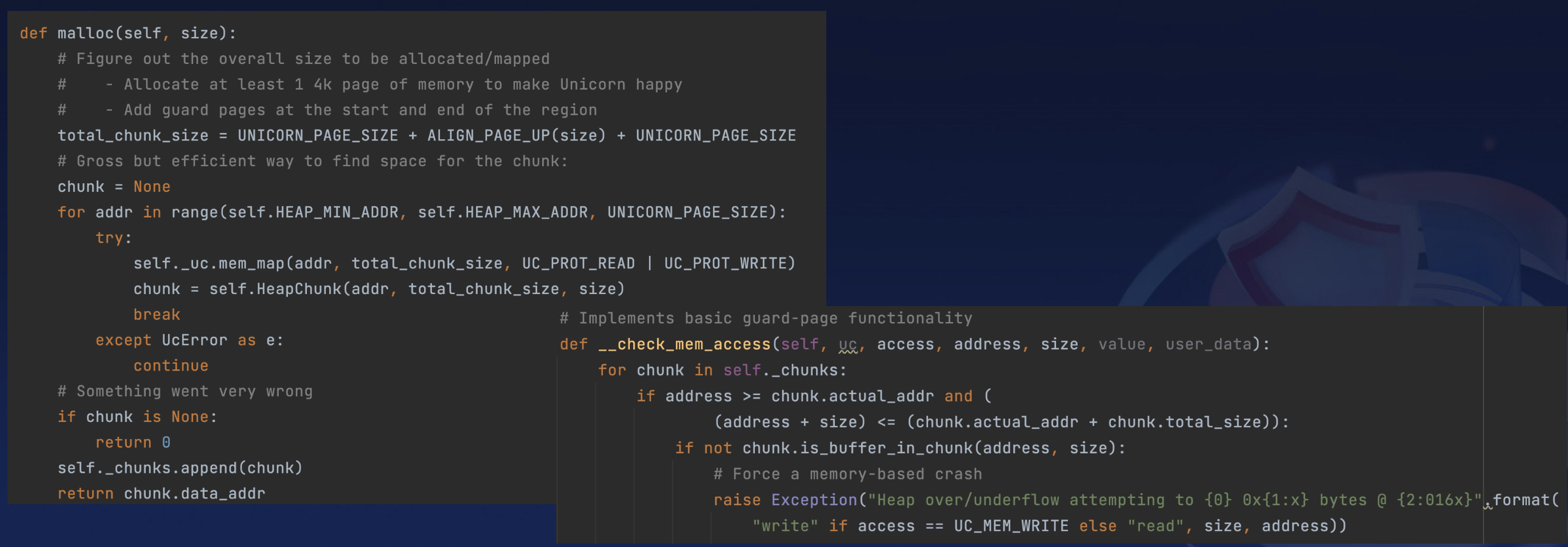

5.2 Implementation of Heap Overflow Detection Strategy in AFL-Unicorn

The AFL-Unicorn’s official GitHub repository now includes a Python-based heap overflow detection implementation, similar in concept to ASAN.

It inserts red zones around allocated heap blocks, triggering an exception upon boundary breaches.

But, it’s just a demo and I don’t suggest you use the code directly because it will cause potential bugs under extreme conditions.

For instance, a basic malloc(0x100) operation might lead to a 0x3000 memory allocation.

- It will first align

0x100to the nearest page size, becoming0x1000. - Additionally, the two allocated redzones will each occupy

0x1000, so an initial request for0x100bytes will ultimately result in a0x3000allocation. This can cause issues under extreme conditions, such as frequent memory allocations.

The reason for this behavior is that the memory allocation uses real-time mmap, and Unicorn’s mmap size must be a multiple of 0x1000.

My fix is straightforward:

- pre-allocate the heap area during the Unicorn initialization process, for example, from

0x10000000to0x40000000. - This way, we can allocate memory blocks of any size.

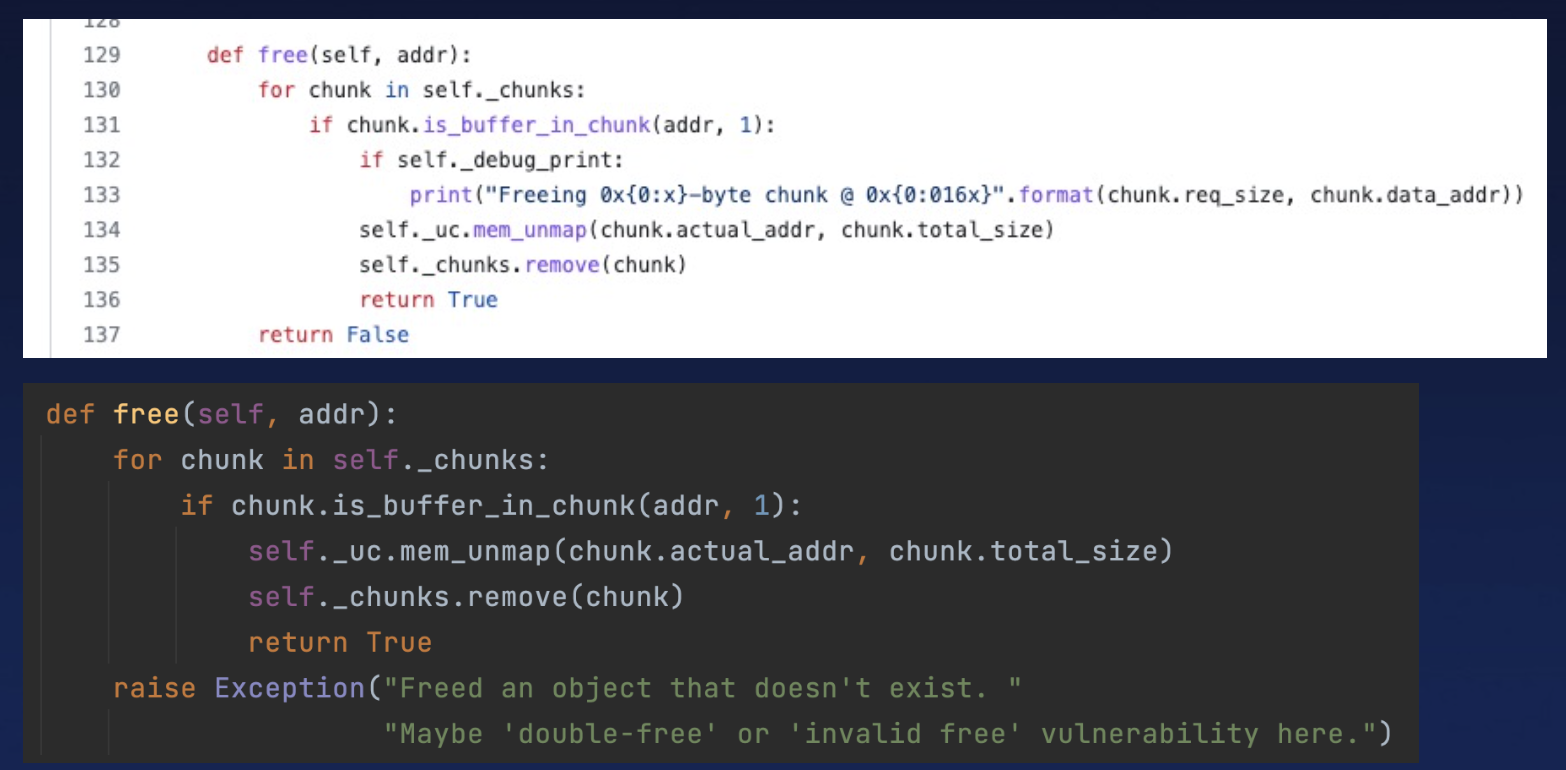

5.3 A Patch To free()

Regarding Free operations, the original code had a minor flaw in handling failed frees, only returning false without accounting for double-free or invalid-free scenarios.

This issue has since been patched.

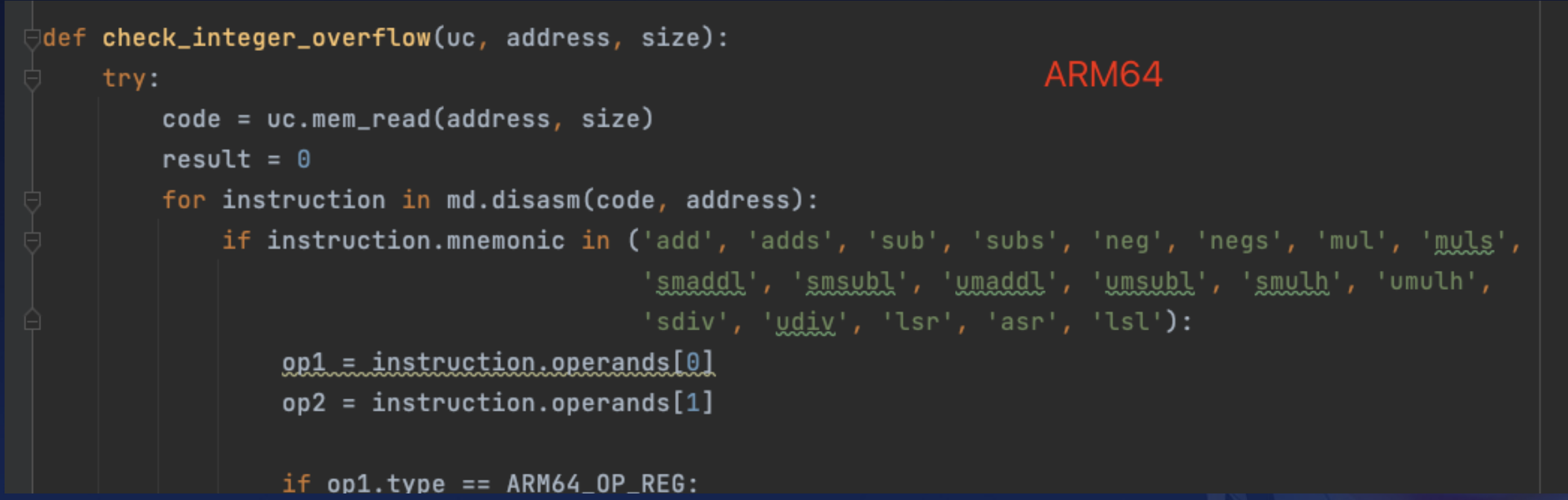

5.4 Implementation of My Integer-overflow Detection

Below is my implementation for integer overflow checks, specifically for the Arm64 instruction set.

5.5 My Solutions to Handle Stateless Fuzzing in AFL-Unicorn

One of the primary challenges with AFL-Unicorn is its stateless Fuzzing nature.

Stateless Fuzzing occurs because AFL-Unicorn saves the memory context and register values before testing a command, then restores everything to the initial state after execution. This approach can lead to missed vulnerabilities, especially if a command’s exploit depends on the outcome of a previous command.

For example:

- When AFL-Unicorn tests

command 1, it first saves the current memory context and all register values. - After

command 1finishes executing, it restores all states and registers to their initial values before testingcommand 2. - If the vulnerability in

command 2depends on the result ofcommand 1, this can lead to missed reports because the result ofcommand 1has been cleared.

To address this, I adopted two solutions.

Initially, I conducted basic research on the TA and found that many TAs have only a few command branches, often just 2 to 5. This led to the first solution:

- Enumerating all commands within a TA and performing permutations and combinations.

- E.g.: {1,2,3,4,5}, {2,3,1,4,5}, {5,4,6,1,2}

- After executing one command chain, I would restore its context.

This brute-force approach was effective, and I did use it to find some vulnerabilities.

However, it has significant drawbacks:

- It dramatically lowers fuzzing efficiency, makes deduplication difficult, and makes it challenging to pinpoint which input data caused a crash.

Therefore, I adopted a second solution:

- Pre-executing and saving the context, essentially using snapshots.

- This method is currently recommended as it avoids the issues of the first approach and enhances overall efficiency and accuracy.

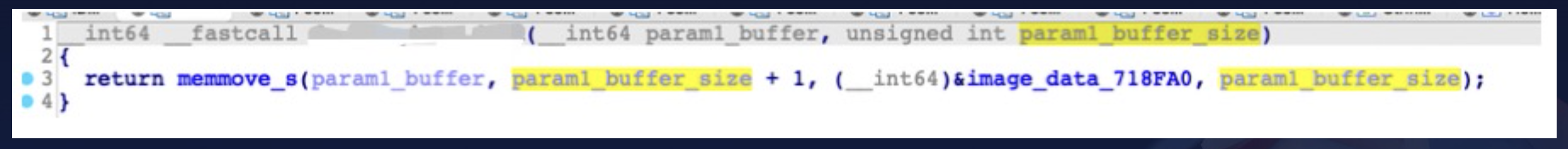

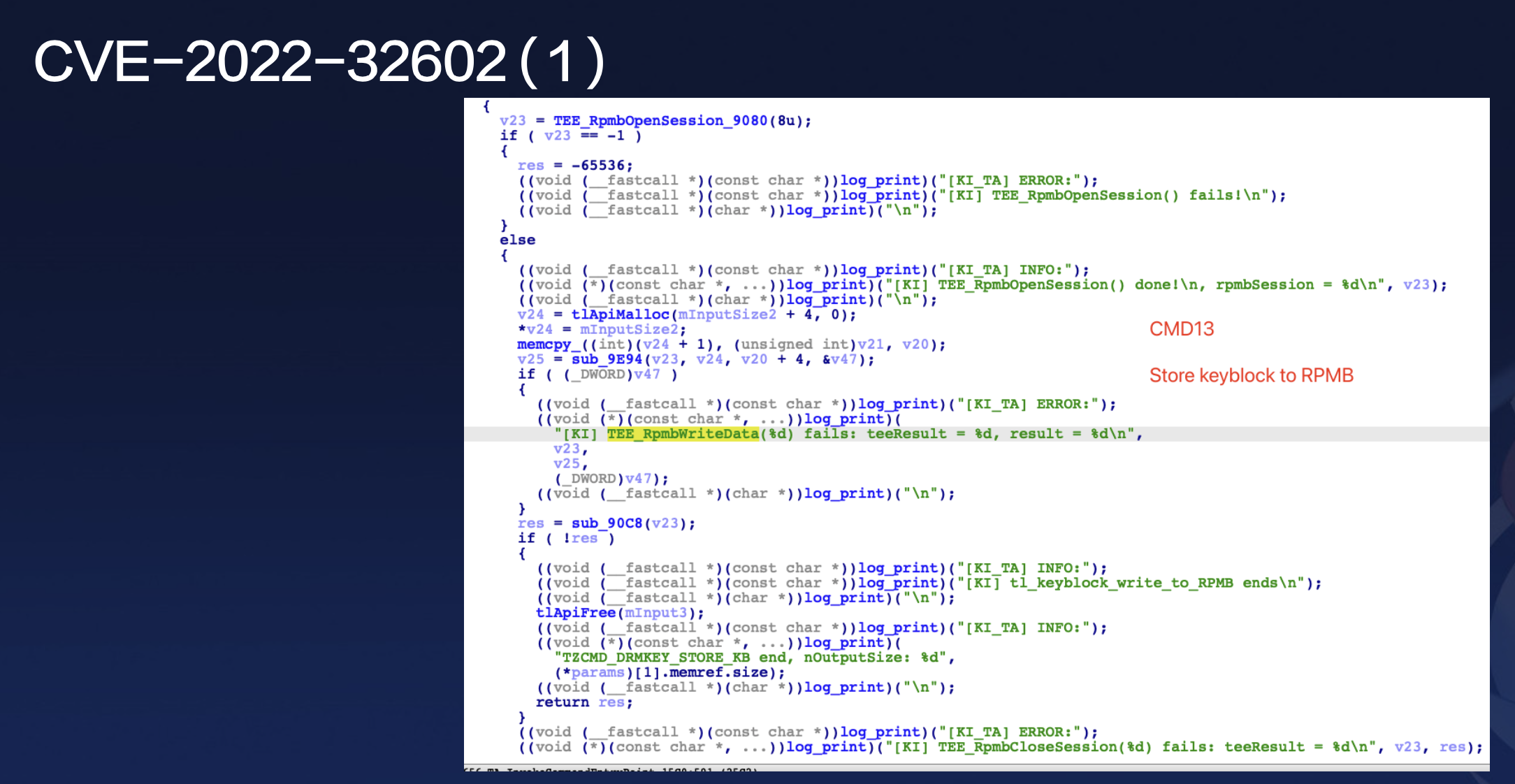

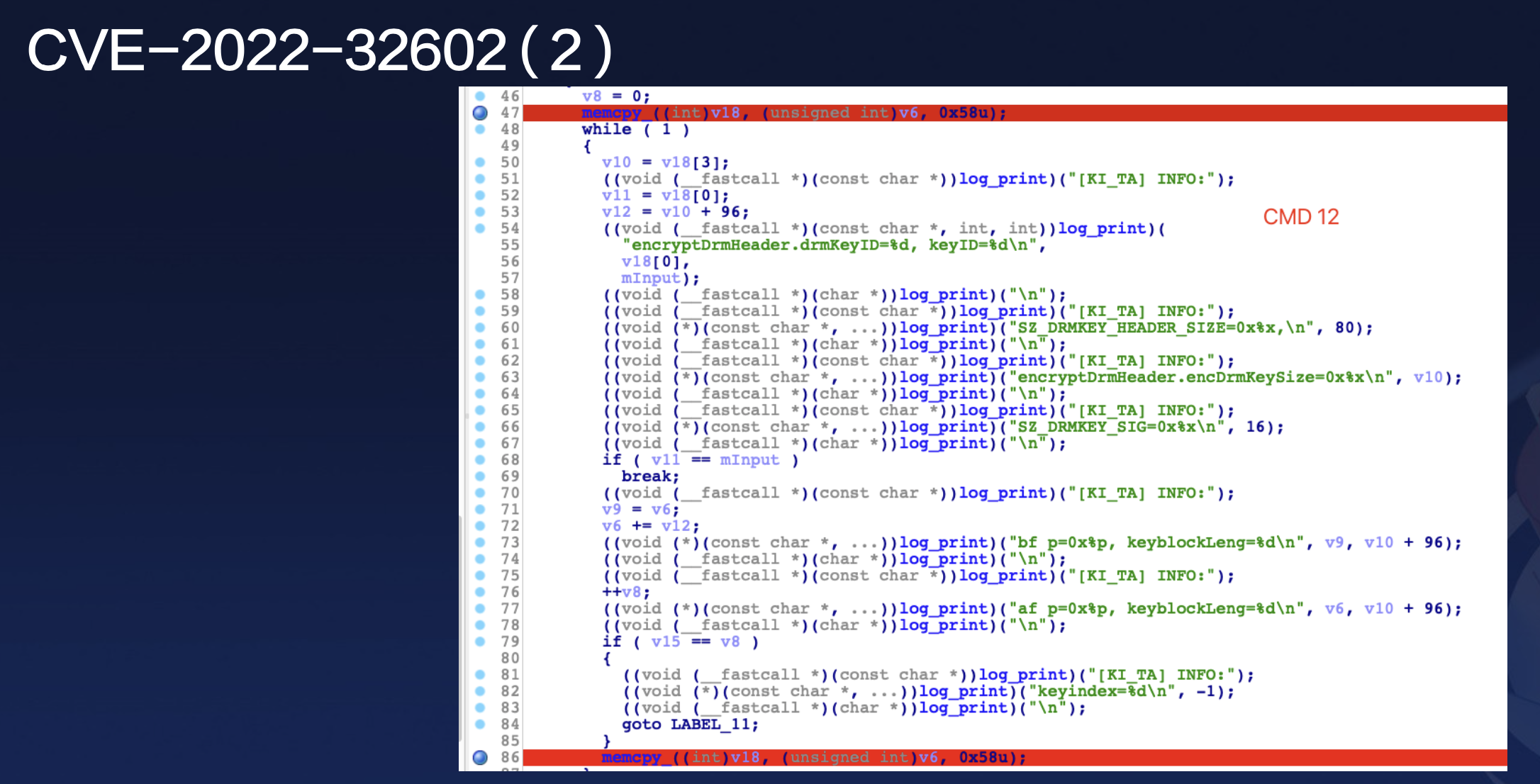

Show case: CVE-2022-32602

I didn’t find the vulnerability when I used the default fuzzing strategy. And when I updated its strategy of fuzzing, I did.

The exploit required first calling command13, insert a keyblock structure into the rpmb.

Then, invoking command12 would cause the TA to read the keyblock structure from rpmb .

The lack of proper validation for the copy loop length resulted in a buffer overflow.

This case is a classic example where the exploitation of command12 depends on the execution result of command13.

6. Attack surfaces of TAs

Next, let’s delve into the analysis of the TA attack surface.

I have to omit the demonstration of these vulnerabilities and cannot disclose their details completely due to the vulnerability disclosure policies of the Android OEMs.

So, in this section, I will focus on sharing my experience.

6.1 Type Confusion

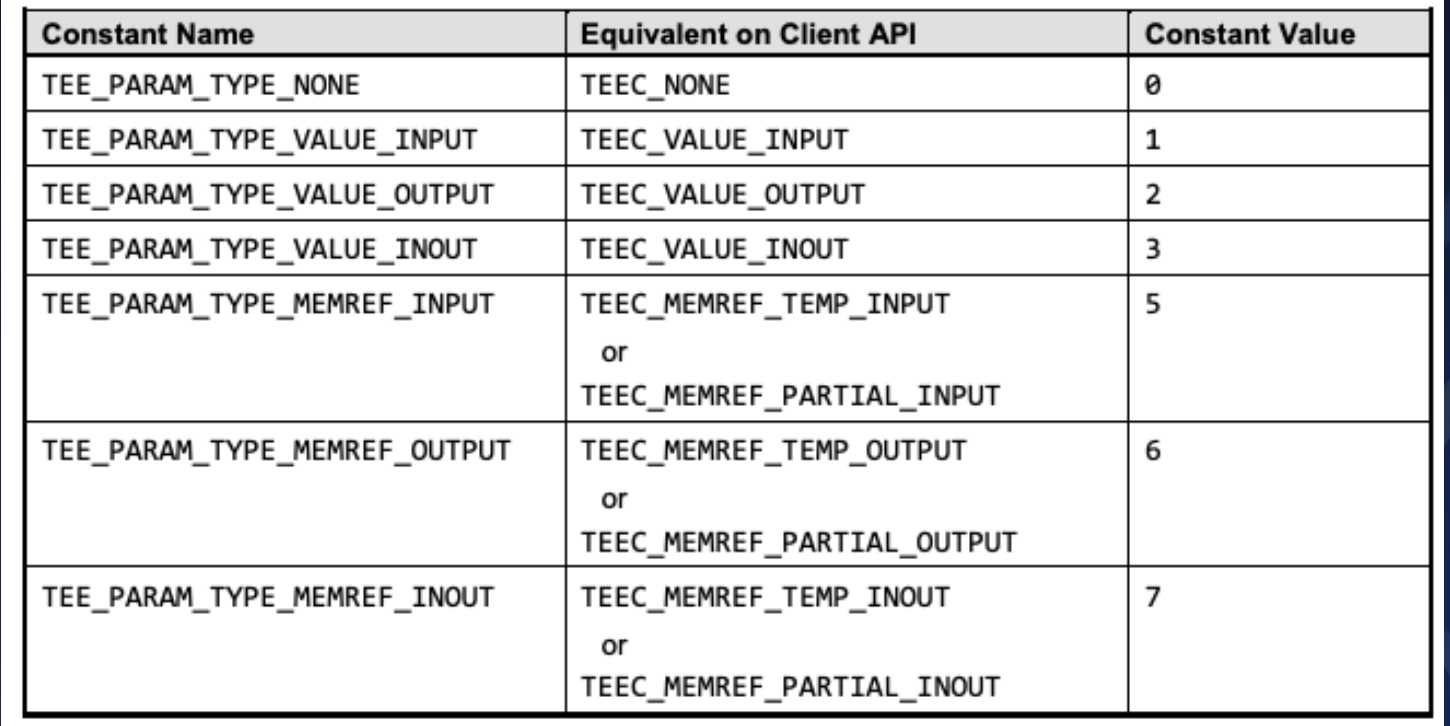

The first one, TA type confusion, is particularly noteworthy.

As mentioned earlier, TAs following the GP standard use the TEE_Param structure for data transmission.

This structure can handle various data types, including both values and buffers.

This flexibility means developers must verify the legitimacy of the external input data carefully.

Failure to do so can lead to type confusion vulnerabilities, treating values as buffers or vice versa.

Unfortunately, in my research, this vulnerability was ubiquitous.

As long as a manufacturer’s TA follows the GP standard, there will be at least one or more instances of type confusion vulnerabilities in their TAs.

These vulnerabilities are straightforward to discover and fix, especially with Fuzzing.

Root Causes, in My Opinion:

- The GP standard grants TA developers excessive authority, allowing them to decide how the TA receives and processes external inputs, thereby exposing potential risks.

- From the perspectives of development efficiency and ease of use, this strategy appears sound.

- However, it places high demands on developers. If developers do not thoroughly understand the

paramtypes, and handle external input unsafely, severe security issues can arise. - For most private TEEs developed by OEMs, I believe it is not necessary to strictly follow the GP standard. It is feasible to eliminate these risky attack surfaces appropriately.

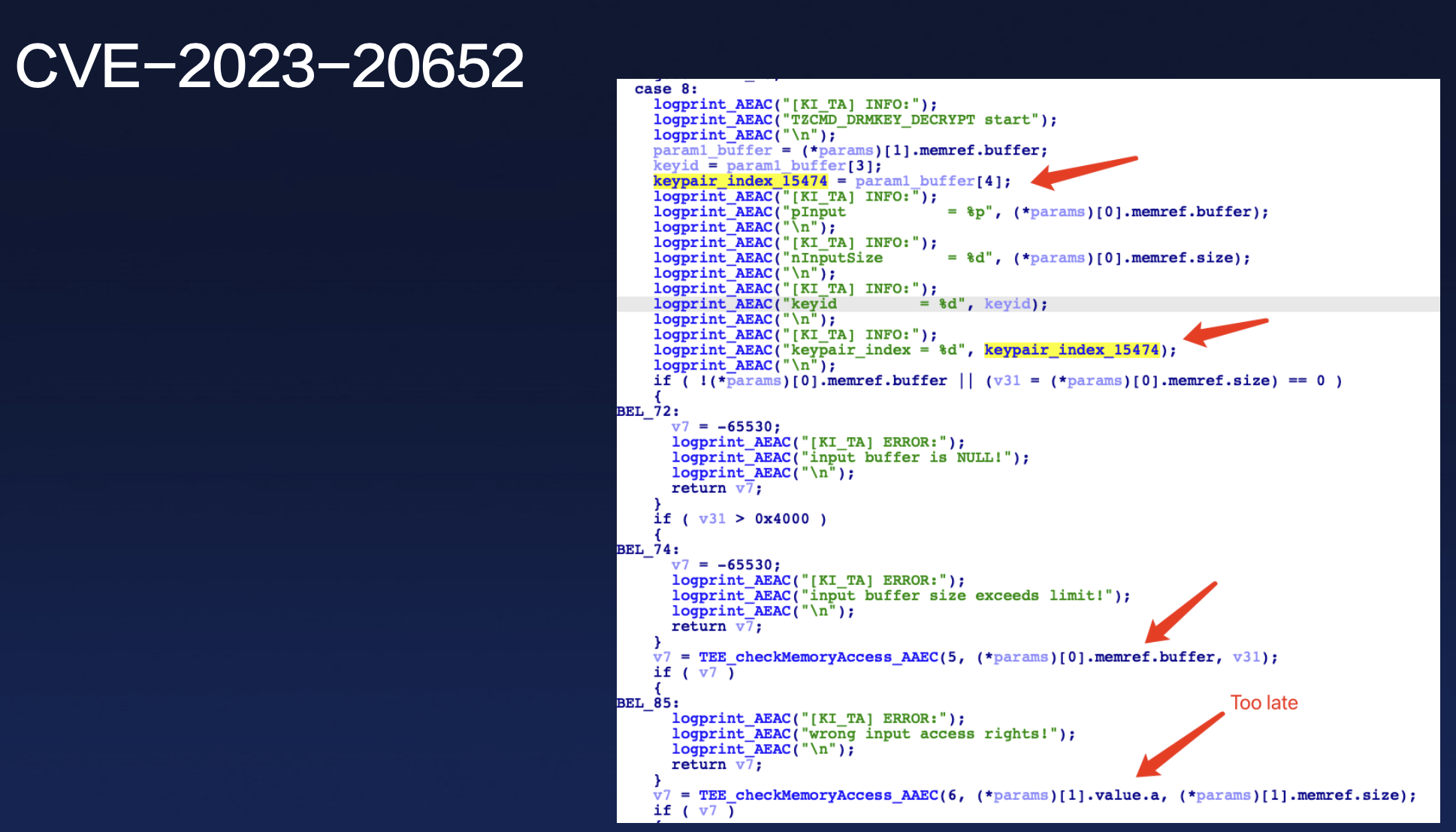

Show case: CVE-2023-20652

A typical example demonstrates this issue.

The developer uses the TEE_CheckMemoryAccess function to verify whether the input is a buffer before executing subsequent code.

However, the developer uses the input before verification, leading to a type confusion vulnerability allowing arbitrary memory reads.

I think there are maybe two developers. The first developer has good security intentions, but the second one doesn’t.

To prevent such type confusion vulnerabilities in TAs, I suggest a development approach that includes validating paramTypes and calling the TEE_CheckMemoryAccess function to prevent illegal inputs.

- A more universal solution might be to encapsulate the type verification function into a SDK, restricting developers to only read data from shared buffers and blocking the

valuestype.

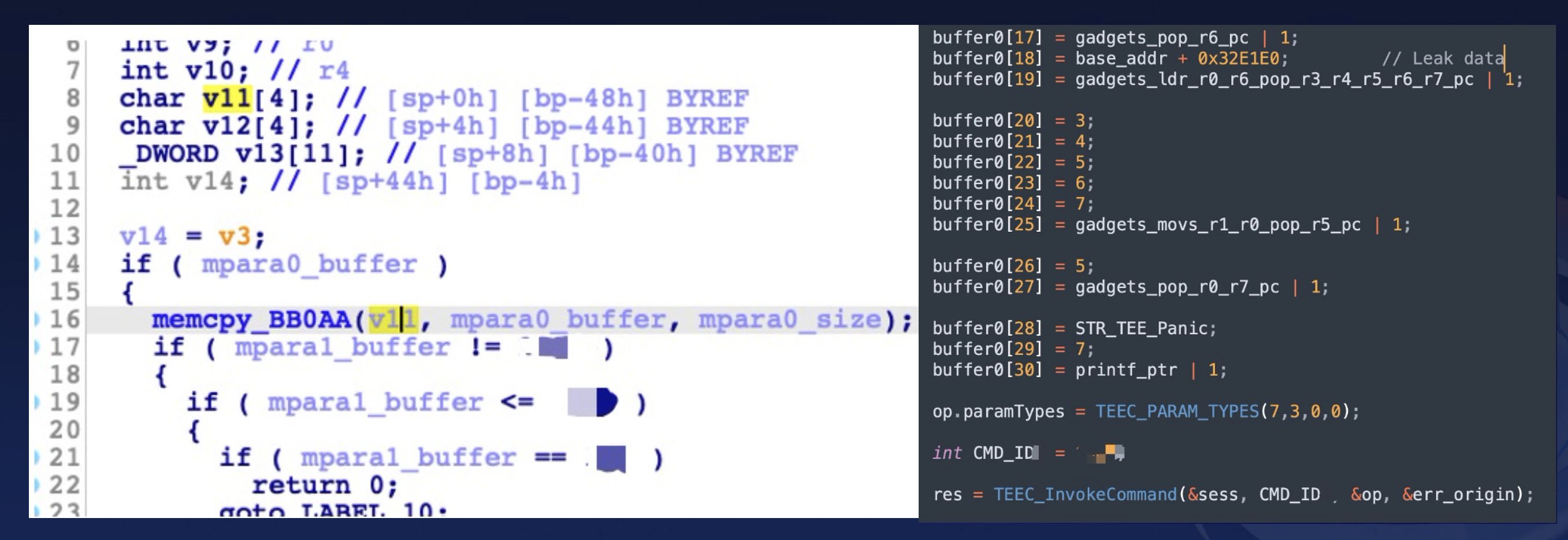

6.2 Memory corruption : Fingerprint TA

Now, returning to classic binary exploitation issues, let’s consider a typical stack overflow in a fingerprint TA.

When conducting security research on vendors’ fingerprint and facial recognition TAs, I discovered some very peculiar cases. The code for these biometric TAs on Android phones is not always written by the phone manufacturers themselves but often comes from the developers of the fingerprint modules. While the phone manufacturers’ code usually adheres to certain security baselines, penetration testing, and SDL, the code from the module developers does not. This results in numerous vulnerabilities in the fingerprint and facial recognition TAs used on many phones.

Originally, these TAs were intended to protect users’ data security, but due to the poor code quality, they end up making the phones more vulnerable to attacks, which is quite counterproductive.

After the exploit, during my further exploration of its memory, I discovered some unique attack points in the fingerprint TA.

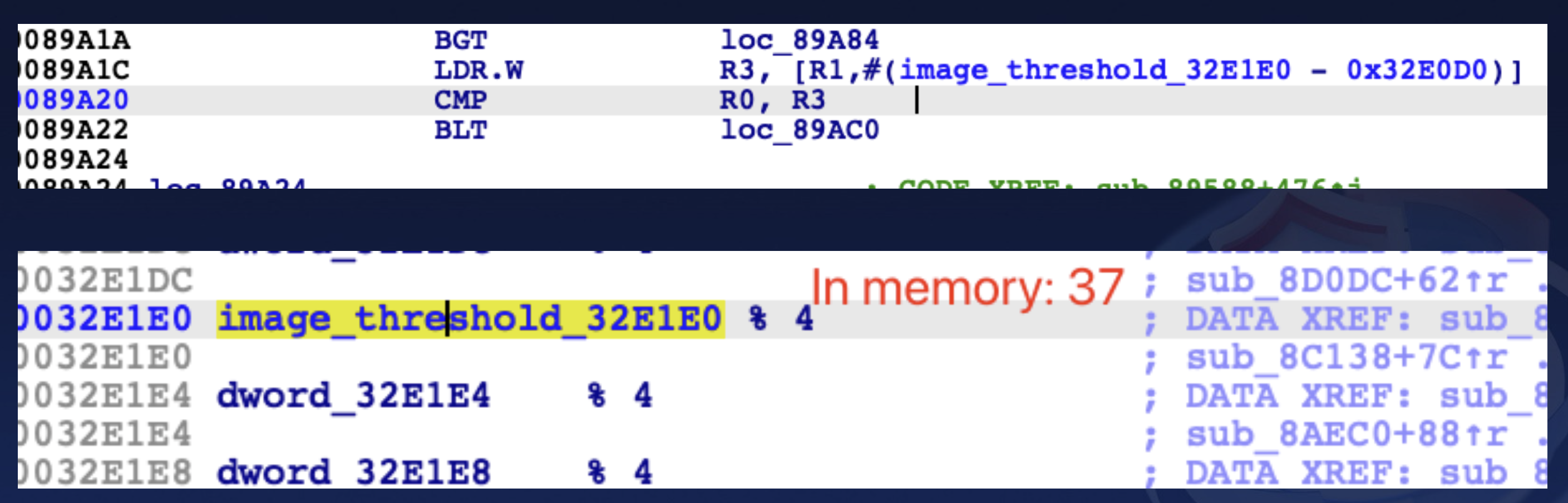

First, we need to understand a concept:

- when a user’s finger presses the fingerprint sensor on the phone to unlock the screen, the sensor sends the user’s fingerprint information to the fingerprint TA.

- The fingerprint TA then compares the input with the locally stored fingerprint template.

- If the match reaches a certain threshold, the system considers it a valid fingerprint and unlocks the phone.

As you can see in the second image below, the matching threshold for the fingerprint TA on this particular phone is 37%.

This means that as long as the similarity reaches 37%, the system will recognize it as a valid fingerprint and unlock the phone.

Although this seems like a very crude strategy, that particular phone had a side-mounted fingerprint sensor located on the power button. The limited verification area made 37% an acceptable threshold.

Now, let’s consider this from an attacker’s perspective.

If we have a type confusion vulnerability that allows arbitrary memory writes, many times we need to put in a lot of effort to construct our own ROP chain, and sometimes our exploit might not even succeed.For example, a vulnerability can help us write a bit 0 to arbitrary address, off by 1 and etc.. But if our target is fingerprint TA or similar TAs, we can attempt to attack these state variables directly to unlock the phone. A clear prerequisite here is that the memory page where these state variables are stored must be writable.

6.3 Information leakage

- Vulnerabilities

- Logs

- Check

/procorcat /proc/kmsg

- Check

Information leakage is another issue, often occurring through logs.

However, most manufacturers have either encrypted or disabled TA logs, raising the bar for security analysis. Yet, developers often leave backdoors for their convenience. I recommend searching for potential exploits in directories like /system, /proc, /vendor, /odm, /products, and /oem.

6.4 Logic bug : Extracting Plaintext Passwords Stored In Phones

Another logical vulnerability involves extracting plaintext passwords stored in phones.

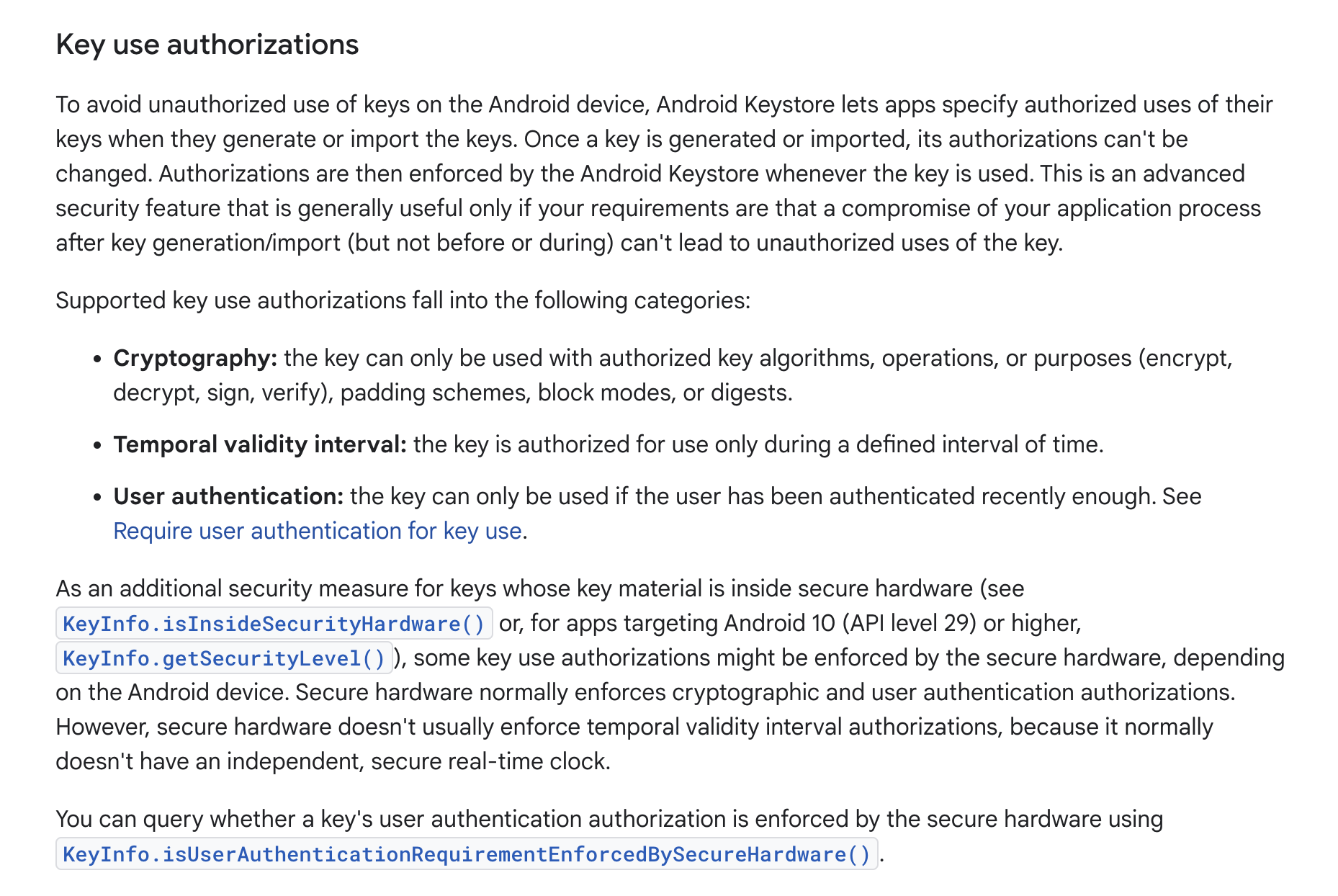

This relates to the Android Keystore system, which provides encryption methods for upper-layer apps.

https://developer.android.com/privacy-and-security/keystore

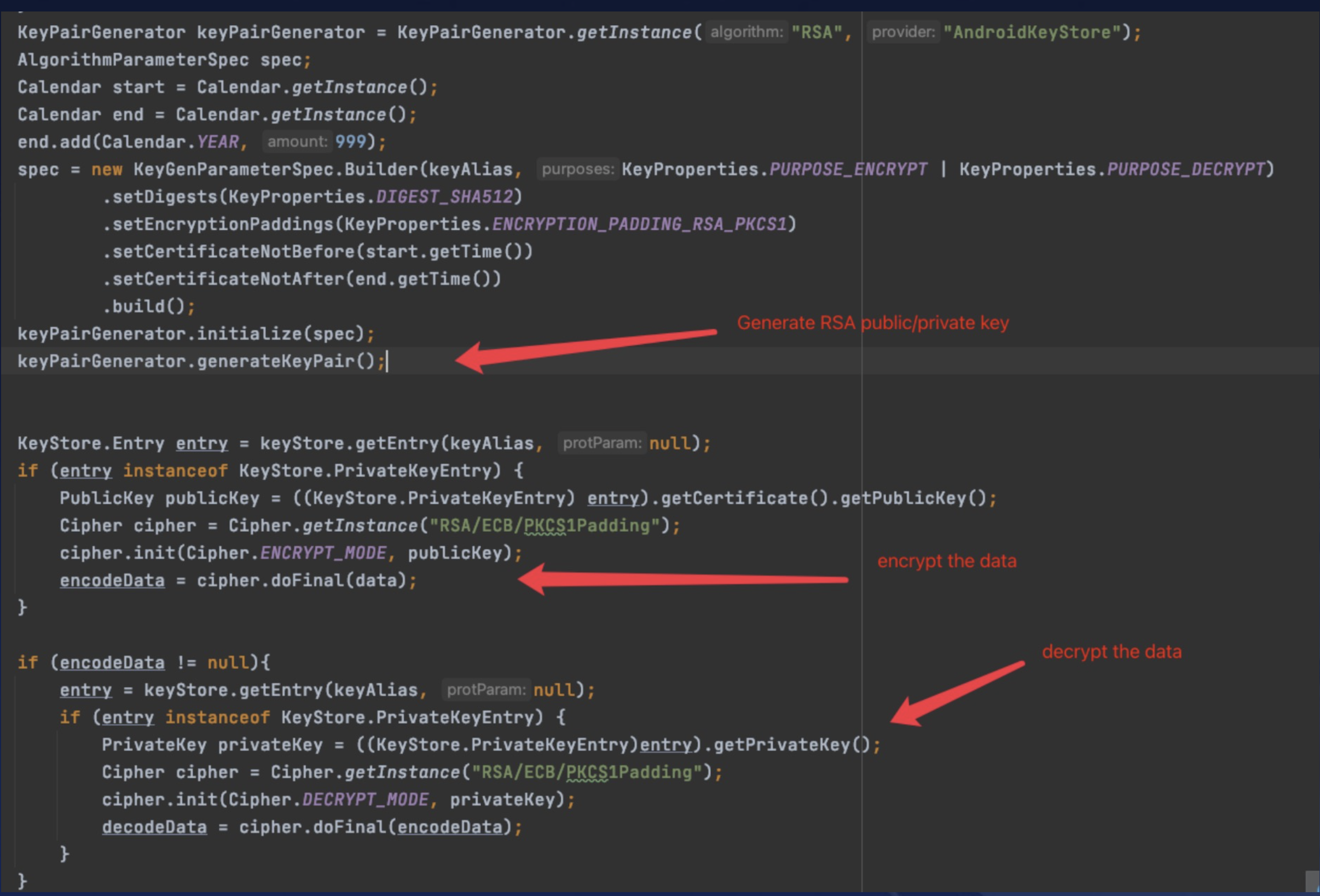

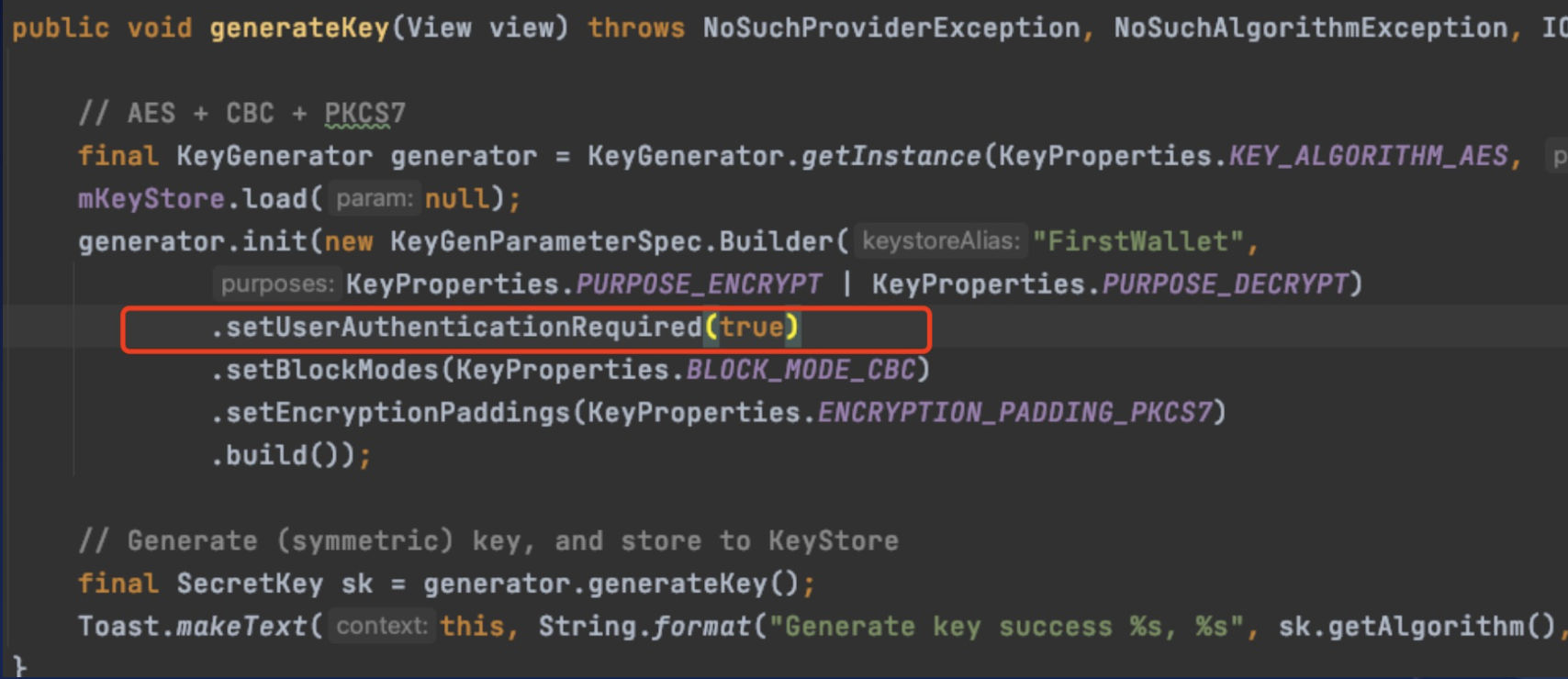

After an app encrypts data using Keystore, the Android system stores the encryption key material in TEE, enhancing key security.

A typical usage involves generating RSA public-private keys through Keystore’s API and then performing encryption and decryption.

However, if an attacker gains the same privileges as the vulnerable app, they can request the Keystore to decrypt all encrypted data of that app.

Therefore, the API should only be used for non-sensitive data.

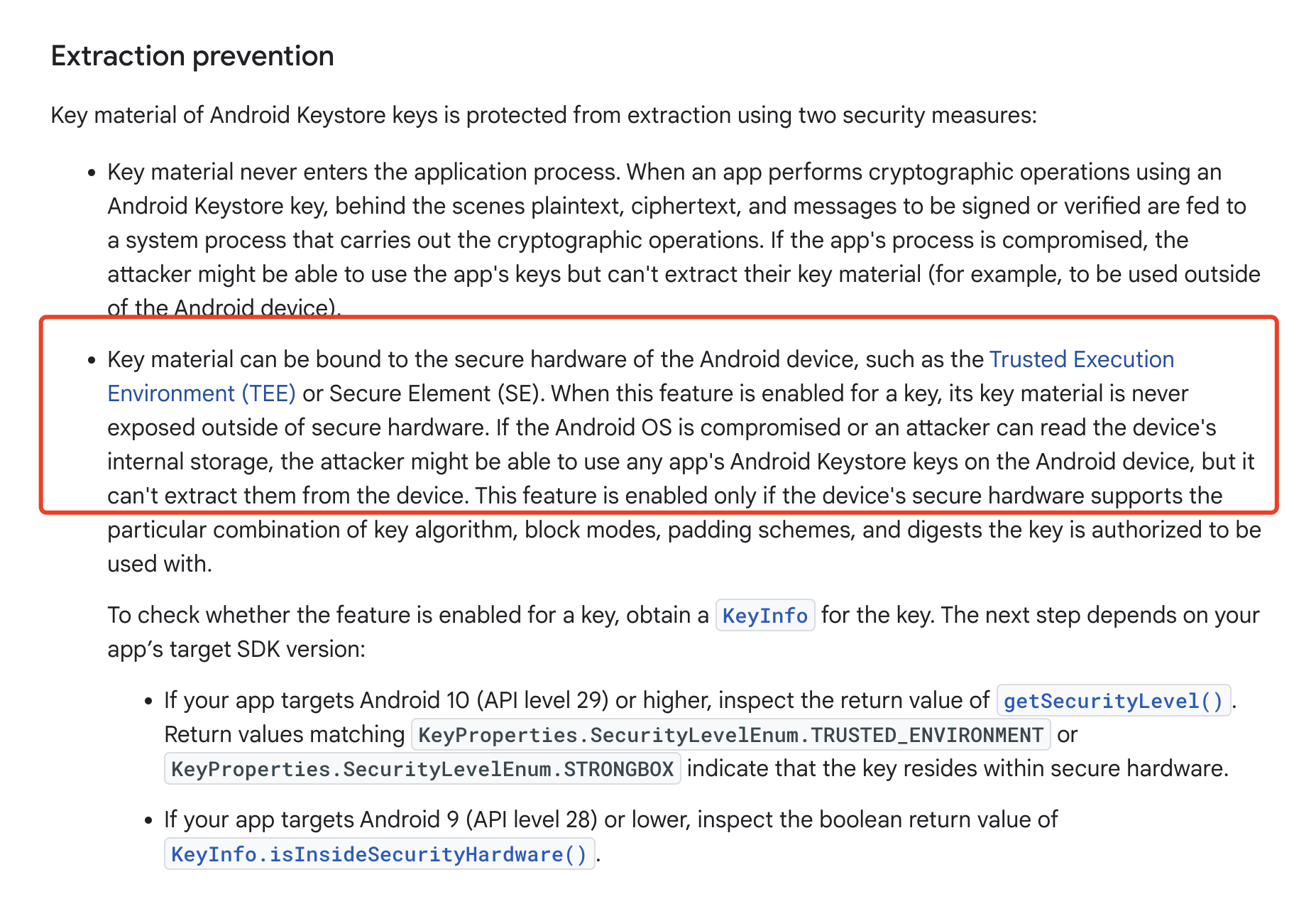

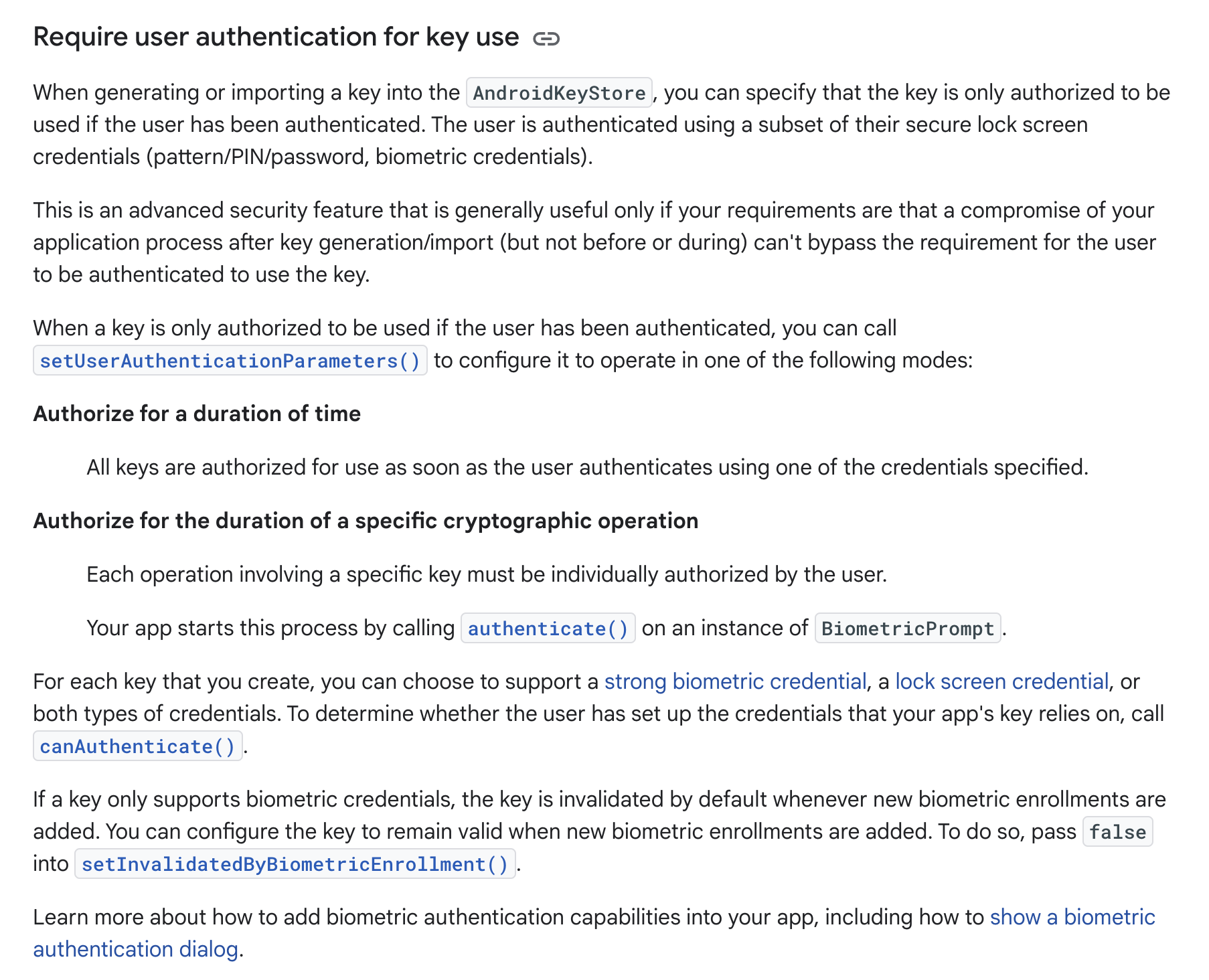

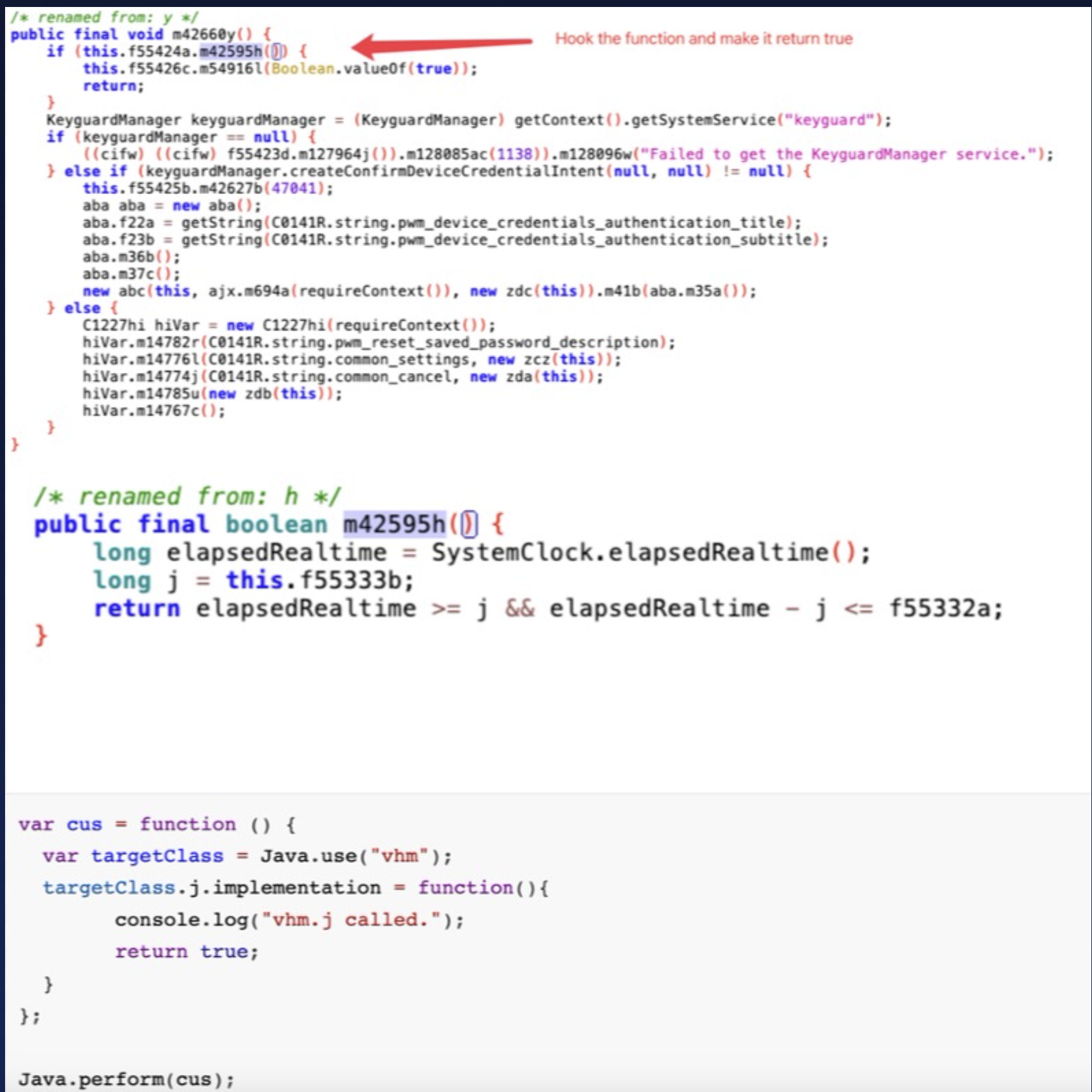

Keystore also supports a higher level of protection based on user identity verification, requiring PIN or fingerprint verification before decrypting data.

These verification processes occur within TEE, ensuring security even if the REE layer is compromised.

I categorize Keystore’s user identity authentication strategies into two types, both ensuring data security even if Android’s root access is compromised.

- User verifies fingerprint or PIN code, TA returns a true or false result and saves the current authorization time.

- Later, when the user triggers data decryption again, the TA checks if the authorization time has exceeded a certain threshold (e.g., 500 or 1000 micro seconds). Only if it is within the valid time frame will it decrypt the data and then return the decryption result to the REE’s CA.

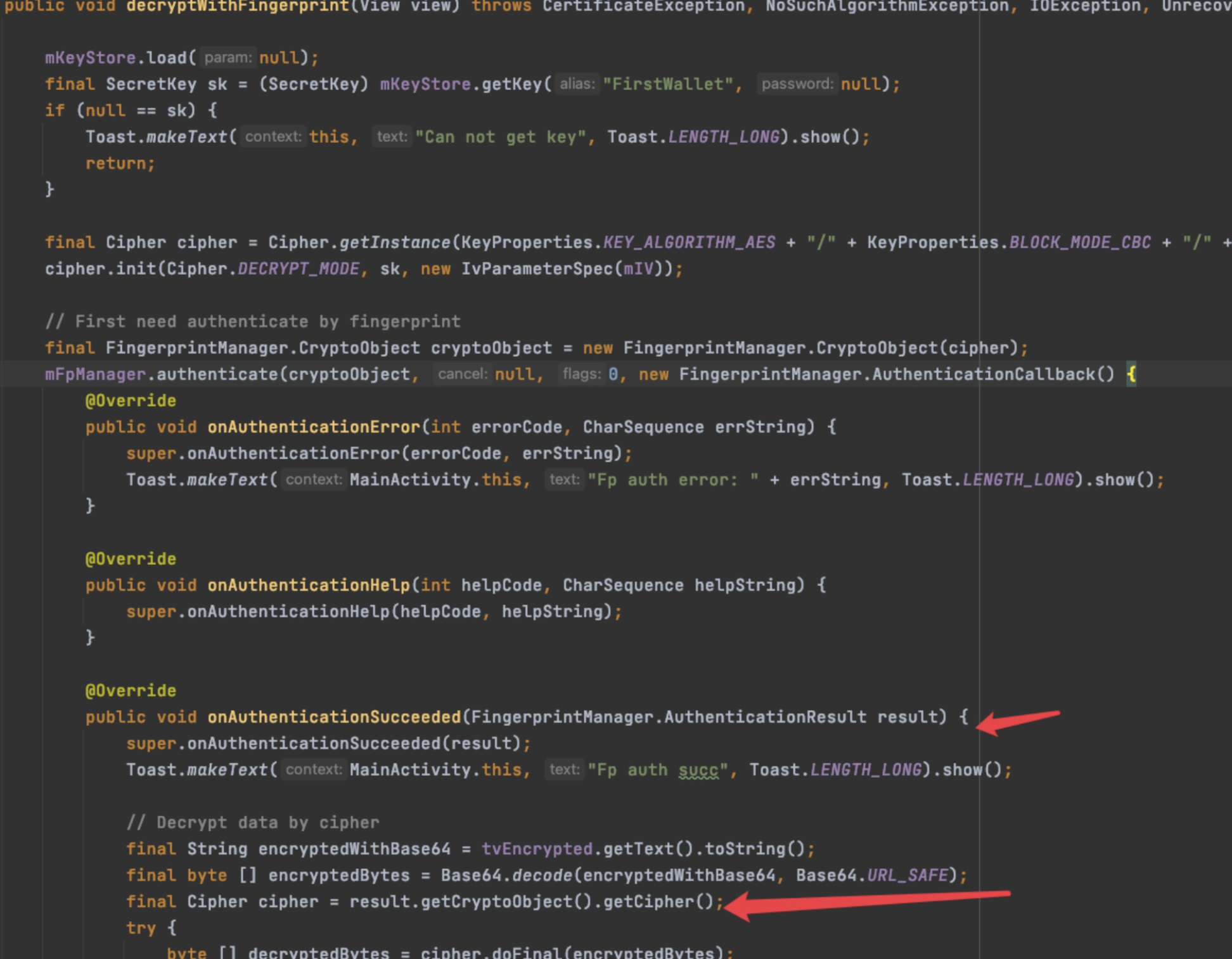

- User verifies fingerprint or PIN code:

- If the verification passes, it triggers the

onAuthenticationSucceededcallback, and the TEE returns the secondary encrypted decryption key to the REE. The REE then sends the encrypted key and ciphertext back to the TEE for decryption.

- If the verification passes, it triggers the

The core of these two strategies takes place in the TEE. The REE layer cannot hook or interfere, thus ensuring that user data remains secure even in a compromised REE.

Here’s a good demo:

https://github.com/stevenocean/UnpasswdDecrypt

Android’s autofill service :

https://developer.android.com/guide/topics/text/autofill-services

Every OEMs can implment their own Autofill Services.

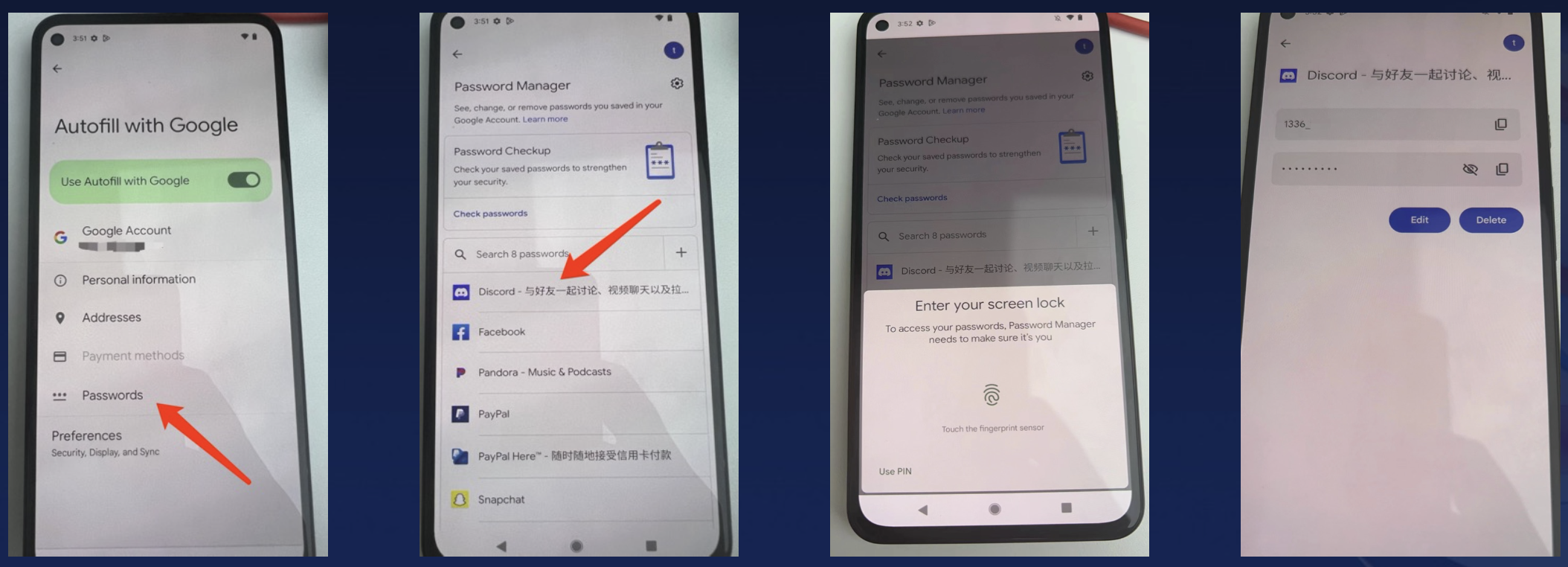

The Autofill Services on Pixel 5a is implemented by GMS (Google Mobile Services).

When a user accesses an app like Discord, the system prompts for fingerprint verification before autofilling saved account credentials.

It looks like GMS is using an authentication-based encryption strategy, but reverse engineering reveals that GMS’s initialization of the encryption key does not set the necessary API for user authentication. The UI process’s fingerprint verification step is independent and does not influence the TEE’s decryption process.

frida -U -l bypass.js -n com.google.android.gms.ui

That is, with system-level privileges, one can extract user data that should be protected by the TEE. The protection level for user passwords is clearly insufficient.

However, I believe this vulnerability is optional for GMS to fix because GMS does not claim to use the highest system security level to protect user passwords.

But if a phone manufacturer explicitly mentions in their security white paper that they will use the highest system security level to protect user passwords, then this vulnerability must be fixed.

Similarly, for Web3 security wallets, this vulnerability must also be addressed.

6.5 Jumper

When we research TAs, we often find that we only have adb shell permissions or untrusted app permissions. But only system-level apps can call the Android TEE driver. This means that we can’t directly talk to the TA we want.

However, let’s think outside the box. TAs are built for using, and some TAs have no permission restrictions due to business needs, this means that any third-party app can directly communicate with the target TA through the interfaces exposed by the pre-installed CA on the Android side, without needing to communicate with the TEE driver.

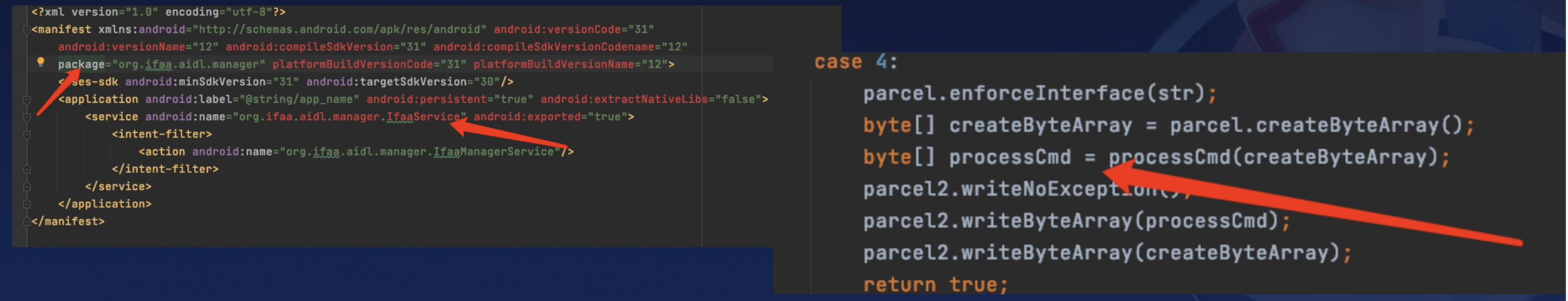

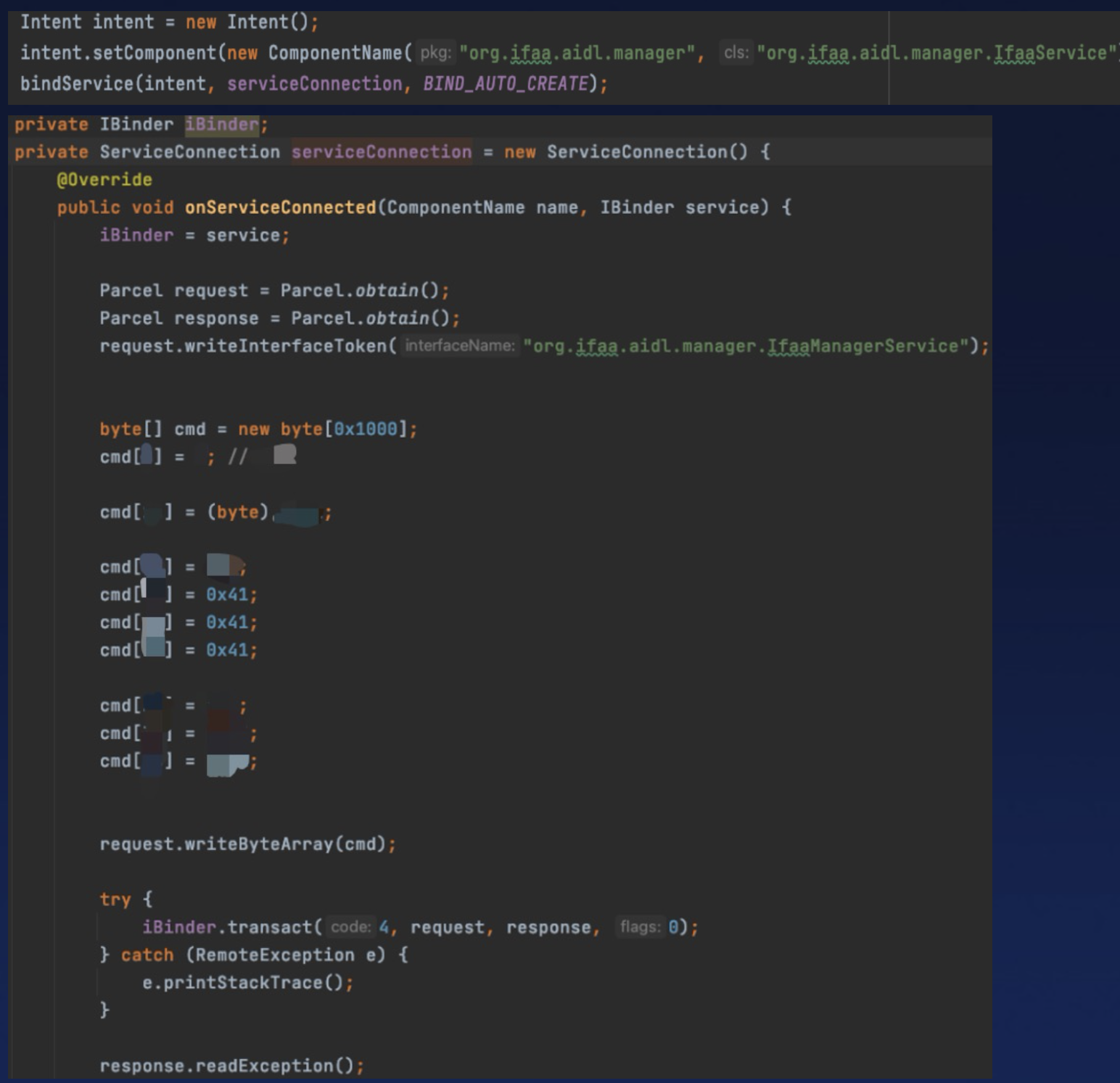

A typical example is IFAA. Simply put, IFAA is a set of standards related to payments, and it also has a set of common components. Each OEM can write their own code on these common components.

https://ifaa.org.cn/bjc/file/1193e9120f0b11e9beb60242c0a82a17?download=true

The OEM’s implementation code has issues, it can lead to any ordinary app being able to write specific content to any file with IFAA TA’s permissions. It also supports reading any file, such as payment keys saved by IFAA.

This vulnerability doesn’t require any special permissions to exploit.

6.6 File Operations

Lastly, let’s address file operations in TEE.

Data storage in TEE can be classified into two ways:

- RPMB

- SFS

RPMB, with limited storage capacity, is unsuitable for large data like fingerprints.

Instead, TEE encrypts large data using AES and stores it in the Android file system, known as the SFS mechanism.

This approach has obvious vulnerabilities:

- Attackers cannot decrypt the data without the AES key, but they can delete or replace the stored data. Additionally, if a TA’s effectiveness depends on the existence of a specific file in the Android file system, this reliance can be easily circumvented. Attackers can inject arbitrary data into the TA. Although the TA cannot read these data, it gives a chance to trigger a memory corruption vulnerability when it parses the external data.

Although path traversal issues do not exist if the TEE uses the default OP-TEE file operation APIs. However, some OEMs develop their own file operation APIs, or even use C/C++ file operation functions. This makes path traversal vulnerabilities possible again.

And Race conditions in multi-instance TAs interacting with the same file are also potential vulnerabilities.

The End

Thanks for reading.

As we can see above, I cannot disclose the details of these vulnerabilities due to the limitations of the vulnerability disclosure policy of the Android OEMs. If they offered big bounties, I might find it acceptable, but they do not.

If I have the ability to research other high-value products, why would I continue researching these low-value products that do not prioritize security and only use it as a marketing gimmick?

So far, my experience with vulnerability research on Apple products has been good. I’m glad to see that.